The Loom is Spinning: Enter the Norse Saga Engine

The sagas of old were carved in bone and stained in red—now, they are forged in code.

The Norse Saga Engine is a groundbreaking RPG experience that uses real-time AI to weave a living, breathing Viking world around your every choice. This isn’t a sanitized fantasy; it is a hyper-realistic dive into the grit of the Viking Age, where history, folklore, and the whispered secrets of the runes collide.

What Awaits You:

- True Authenticity: Built on a foundation of genuine Norse lore, religious practices, and the complex social structures of the era.

- Visceral Interaction: Advanced, adult-oriented AI characters that respond with human-like nuance, memory, and depth.

- The Power of Seiðr: A low-fantasy world where magickal practices and Norse spirituality aren’t just mechanics—they are the atmosphere.

- Novel-Quality Narrative: Every session generates an interactive historical fiction masterpiece, tailored to your path.

The Norns are weaving a new thread, and the architecture of the soul is being mapped. This project is developing rapidly—prepare to claim your place in the saga.

Stay tuned. The high tide is coming.

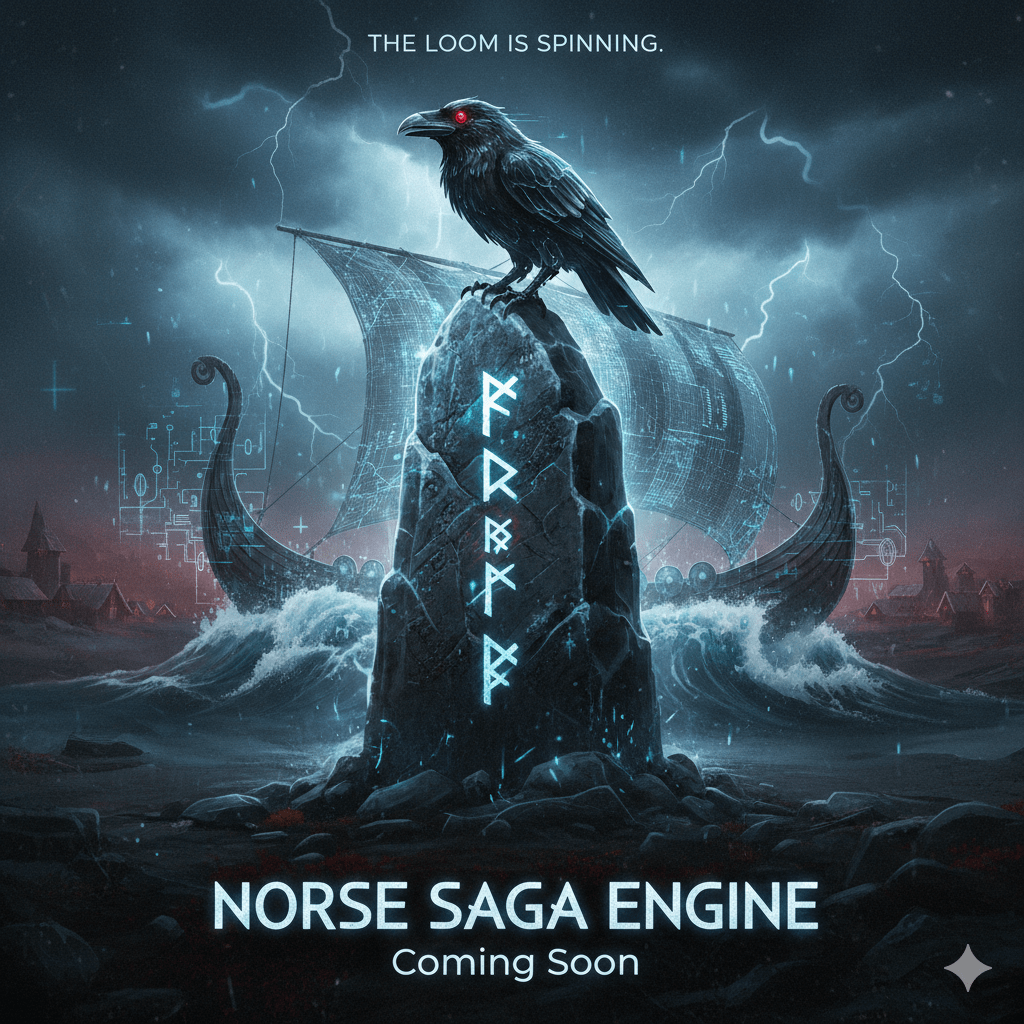

Yggdrasil: The World Tree and Its Nine Realms

Article by Eirynth Vinterdóttir

Introduction: The Cosmic Ash at the Heart of Norse Belief

In the rich tapestry of Norse mythology, Yggdrasil stands as the monumental axis mundi, the immense World Tree that binds the cosmos together in a vast, living network of existence. Often depicted as a mighty ash tree whose branches stretch to the heavens and roots delve into the primordial depths, Yggdrasil embodies the ancient Norse understanding of reality as an interconnected whole, where every realm, being, and force pulses with vitality and interdependence. The name “Yggdrasil” itself derives from Old Norse roots, meaning “Odin’s Horse” or “the Steed of the Terrible One,” alluding to the Allfather’s sacrificial hanging upon its branches to gain the wisdom of the runes—a profound act of endurance and quest for knowledge that mirrors the Viking spirit of facing trials to forge strength.

For the ancient Norse peoples, Yggdrasil was not merely a symbolic construct but a living entity, central to their worldview. It represented the enduring cycle of life, death, and renewal, much like the longships that carried Vikings across stormy seas or the sturdy halls that withstood harsh winters. This cosmology fostered a sense of resilience and harmony with the natural order, encouraging individuals to navigate fate with courage and honor. The tree’s vast canopy sheltered gods and giants alike, while its roots drew sustenance from sacred wells, illustrating the Viking value of balance between order and chaos, prosperity and peril.

Modern Norse Paganism revives this vision of Yggdrasil as a profound metaphor for personal and communal existence. Practitioners draw upon it to cultivate self-reliance, recognizing that just as the tree withstands tempests, so too must one stand firm amid life’s uncertainties. Through meditation, ritual, and storytelling, the World Tree serves as a guide to understanding one’s place in the grand weave of wyrd—the intricate fabric of destiny spun by the Norns. This article delves deeply into Yggdrasil’s structure, its nine realms, and the cultural values it inspired among the Vikings, offering a comprehensive exploration of this cornerstone of Norse spiritual heritage.

Historical and Mythological Foundations

The lore of Yggdrasil emerges from the oral traditions of the Viking Age, preserved in written form through the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, key texts compiled in 13th-century Iceland. The Poetic Edda, a collection of anonymous poems likely dating back to the 9th and 10th centuries, vividly describes the tree in the poem Grímnismál, where Odin recounts its grandeur to a mortal king: “Yggdrasill is the foremost of trees; an ash it is, / from it dew drips for the valleys; / ever green it stands by Urd’s well.” This imagery evokes the tree’s eternal vitality, a beacon of stability in a world of flux.

Snorri Sturluson, in his Prose Edda, expands on this in the Gylfaginning, portraying Yggdrasil as the central pillar supporting the heavens, with its branches encompassing the sun, moon, and stars. Archaeological evidence supports these accounts: runestones from Sweden and Denmark depict tree-like motifs intertwined with serpents and stags, symbolizing the creatures that inhabit Yggdrasil. Viking ship burials, such as the Oseberg ship from Norway (9th century), include wooden carvings resembling cosmic trees, suggesting that artisans viewed the vessel as a microcosm of Yggdrasil—a vessel for the soul’s journey through the realms.

The Vikings integrated Yggdrasil into their daily ethos. Seafarers might carve its likeness on prows for protection during voyages, invoking the tree’s steadfastness against Jörmungandr, the world-serpent gnawing at its roots. Farmers honored it through offerings at sacred groves, recognizing the tree’s role in the fertility cycles that sustained their longhouses. This practical reverence underscored the cultural value of reciprocity: just as the tree nourished the worlds, so too did humans offer mead or grain in return, ensuring communal prosperity and honoring the bonds of frith—sacred kinship peace.

In sagas like the Völsunga Saga, Yggdrasil appears metaphorically as the backdrop for heroic deeds, where warriors like Sigurd draw strength from its symbolic endurance. These narratives taught that life’s trials, like the tree’s struggles with beasts and decay, forge character through perseverance. Modern Norse Pagans study these sources to reclaim this heritage, using Yggdrasil as a meditative focus to embody Viking resilience—standing tall amid personal “storms” with unyielding honor.

The Structure of Yggdrasil: Roots, Trunk, and Branches

Yggdrasil’s form is a marvel of cosmic architecture, its massive trunk rising from the center of creation, branches piercing the skies, and roots anchoring the underworlds. The Prose Edda describes it as an ash tree of unparalleled size, its leaves forming a canopy that shelters the gods’ halls and its bark etched with runes of power. Dew from its boughs falls as life-giving rain to Midgard, symbolizing the nourishment that flows from divine to mortal realms—a reminder of the Viking principle of generosity, where abundance shared strengthens the whole.

Three sacred wells sustain the tree, each at the base of a root and embodying profound mysteries. The Well of Urd, guarded by the Norns, is the wellspring of fate, where past, present, and future converge. Here, the threads of wyrd are spun, teaching that destiny is not rigid but woven through choices, much like a Viking chieftain negotiating alliances at the thing. The Well of Mimir holds the wisdom Odin sought, its waters granting prophetic insight to those who sacrifice for knowledge—echoing the cultural valorization of cunning and sacrifice for the greater good.

The third well, Hvergelmir, bubbles in Niflheim’s depths, source of eleven rivers that course through the worlds, representing the primal flow of life from chaos. Creatures inhabit Yggdrasil, adding dynamism: the squirrel Ratatoskr scurries along its trunk, carrying messages between eagle (at the top, symbolizing lofty vision) and Nidhogg (the dragon gnawing roots, embodying destructive forces). Four stags—Dain, Dvalin, Duneyr, and Durathror—browse its branches, their horns symbolizing renewal. These elements illustrate the Viking view of existence as a balanced struggle: growth amid erosion, vigilance against decay, fostering self-reliance in the face of inevitable trials.

In ritual practice, Vikings might have circumambulated sacred trees or oaks, mimicking Yggdrasil’s circuits to invoke its protective embrace. Today, practitioners visualize the tree during meditations, tracing its form to center themselves, drawing on its structure to cultivate inner fortitude and harmony with natural cycles.

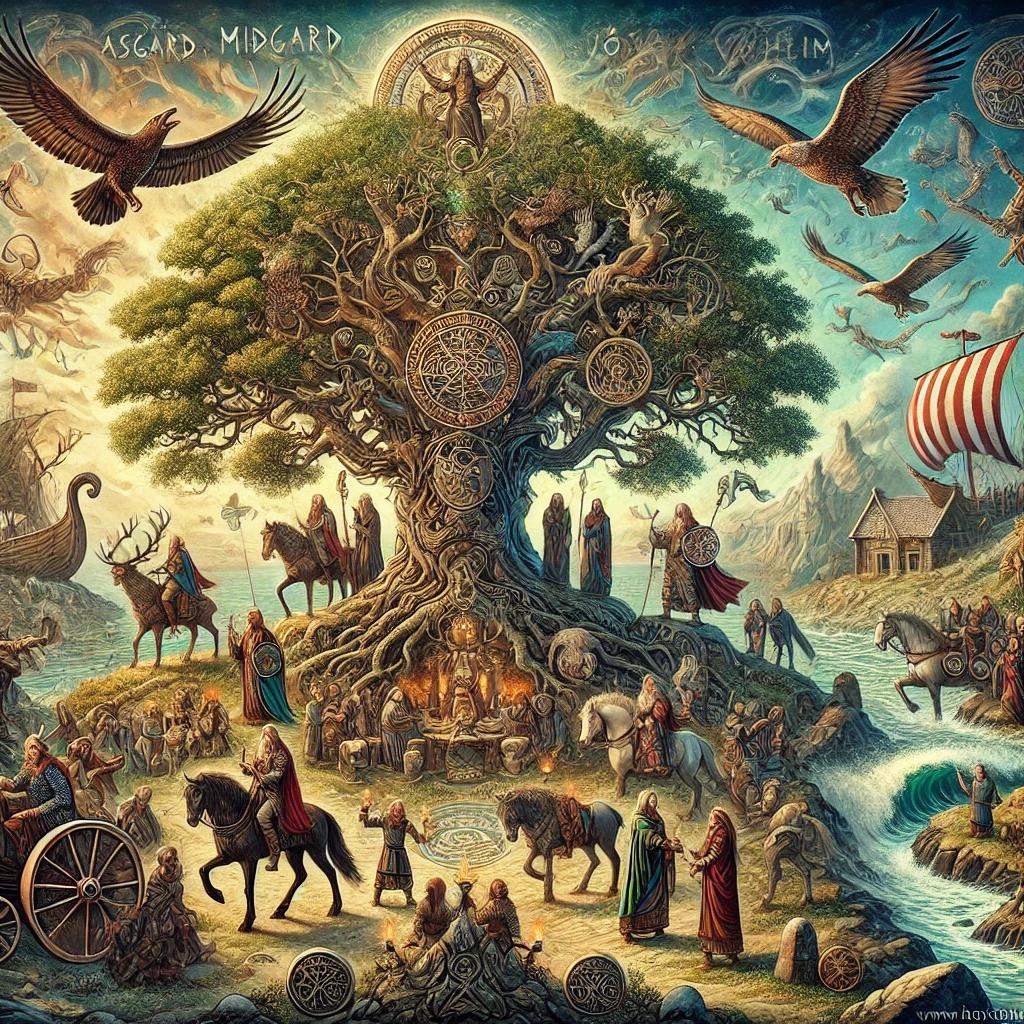

The Nine Realms: Interwoven Worlds of Wonder and Peril

Yggdrasil connects nine distinct realms, each a unique domain of existence, reflecting the multifaceted Norse cosmos. These worlds are not isolated heavens or hells but interdependent spheres where gods, humans, and other beings interact, underscoring the Viking emphasis on interconnectedness and adaptability.

Asgard: The Realm of the Aesir Gods

High in Yggdrasil’s branches lies Asgard, the shining fortress of the Aesir, gods of sovereignty, war, and wisdom. Ruled by Odin from his hall Valhalla—where einherjar (fallen warriors) feast in preparation for Ragnarök—Asgard represents ordered power and heroic destiny. The rainbow bridge Bifrost, guarded by Heimdall, links it to Midgard, symbolizing the vigilant watch over mortal affairs.

Vikings revered Asgard as the pinnacle of aspiration, where oaths were sworn and battles planned. Its halls, like Gladsheim (assembly) and Vingolf (for goddesses), embodied communal decision-making, akin to the thing assemblies that resolved disputes with honor. Modern Norse Pagans invoke Asgard in rituals for guidance in leadership, meditating on its light to embody courage and strategic foresight, values central to Viking warriors who led raids with calculated bravery.

Vanaheim: The Lush Domain of the Vanir

Nestled amid fertile groves in Yggdrasil’s mid-branches, Vanaheim is home to the Vanir gods of fertility, prosperity, and the earth’s bounty. Frey, Freyr, and Njord dwell here, overseeing cycles of growth and harvest. This realm’s gentle landscapes contrast Asgard’s fortresses, highlighting the balance between martial vigor and nurturing abundance.

The Vanir-Aesir war, resolved through hostage exchange (including Freyja), teaches reconciliation and mutual respect—core Viking values in forging alliances after conflict. Farmers offered to Vanaheim’s deities for bountiful yields, ensuring self-reliance through the land’s gifts. Contemporary practitioners honor Vanaheim with seasonal thanksgivings, planting seeds or brewing ale to celebrate reciprocity, fostering gratitude that sustains kin and community.

Alfheim: The Radiant Home of the Light Elves

Perched lightly in the upper branches, Alfheim glows with ethereal beauty, realm of the ljósálfar—light elves—who embody grace, artistry, and inspiration. Ruled by Freyr, it is a place of luminous meadows and crystalline streams, where creativity flows freely.

Vikings associated Alfheim with poetic vision, as skalds drew from its essence to compose sagas that preserved history and valor. This realm inspired the cultural pursuit of beauty in craftsmanship, from intricate jewelry to runic verses. In modern practice, Alfheim guides artistic endeavors, with Heathens crafting talismans or reciting poetry under the stars to channel its light, promoting the Viking ideal of expressing honor through skilled creation.

Midgard: The Human World and Its Boundaries

Encircling Yggdrasil’s trunk, Midgard is the realm of humanity, forged by Odin, Vili, and Ve from the giant Ymir’s body. Bordered by an ocean and the encircling wall of eyebrows (from Ymir), it is the stage for mortal lives, where wyrd unfolds through toil and triumph.

Vikings saw Midgard as the proving ground for virtues like courage and hospitality, where longhouses hosted travelers and fields were tilled with steadfast labor. The world-serpent Jörmungandr coils around it, reminding of peril’s proximity. Modern Norse Pagans view Midgard as the heart of practice, performing daily rites to honor its cycles, embodying self-reliance by tending homes and gardens as extensions of the sacred earth.

Jotunheim: The Wild Mountains of the Giants

In Yggdrasil’s rugged outskirts, Jotunheim sprawls as the domain of the jötnar—giants representing primal forces of nature and chaos. Utgard, home of Utgard-Loki, features towering mountains and untamed wilds, where strength is tested.

The giants, kin to the gods yet often adversarial, symbolize necessary disruption; Thor’s battles with them affirm the Viking value of confronting chaos with unyielding might. Yet alliances, like Skadi’s marriage to Njord, show respect for raw power. Practitioners meditate on Jotunheim to build resilience, facing personal “giants” with the honor of a steadfast defender.

Svartalfheim (Nidavellir): The Shadowy Forges of the Dark Elves and Dwarves

Deep in Yggdrasil’s roots lies Svartalfheim, or Nidavellir, the subterranean realm of svartálfar (dark elves) and dwarves—master smiths who craft wonders like Mjölnir and Odin’s ring Draupnir. Its caverns echo with hammers, birthing treasures from earth’s depths.

Vikings prized dwarven craftsmanship as the pinnacle of skill and ingenuity, values evident in ornate weapons and jewelry that denoted status through merit. This realm teaches the cultural ethic of diligent labor yielding enduring legacy. Modern Heathens honor it by forging tools or jewelry, invoking dwarven precision to cultivate self-reliance through hands-on creation.

Niflheim: The Misty Void of Ice and Fog

One of Yggdrasil’s deepest roots plunges into Niflheim, the primordial realm of ice, mist, and cold darkness. Source of the Hvergelmir spring, it birthed the frost giants and represents the chill of beginnings and endings.

Vikings endured Niflheim’s essence in Scandinavian winters, using it to temper resolve—hospitality warmed halls against the frost. Its well teaches reflection in stillness, a value for introspection amid hardship. In practice, Heathens confront Niflheim through winter solstice rites, emerging renewed, embodying Viking endurance.

Muspelheim: The Blazing Realm of Fire

Opposite Niflheim, Yggdrasil’s root taps Muspelheim, the fiery domain ruled by Surtr, whose sword guards the world’s fiery edge. Sparks from its flames ignited creation, symbolizing passion and destruction.

Thor and other gods battle Muspelheim’s forces at Ragnarök, highlighting courage against overwhelming odds—a Viking hallmark. This realm inspires controlled fervor in pursuits, balancing destruction with renewal. Modern rituals invoke its spark for motivation, fostering the value of bold action tempered by wisdom.

Helheim: The Underworld of the Dead

Beneath Yggdrasil lies Helheim, ruled by Hel, daughter of Loki, where ordinary dead reside in a shadowed hall. Not a place of torment but quiet repose, it honors the finality of life with dignity.

Vikings buried kin with grave goods for the journey, valuing remembrance through sagas. Helheim teaches acceptance of mortality, strengthening communal bonds via ancestor veneration. Practitioners offer to it during remembrance rites, upholding hospitality to the departed and the enduring honor of legacy.

Interconnections and the Balance of the Worlds

Yggdrasil’s realms interlink through paths like Bifrost and roots, illustrating the Norse view of unity in diversity. Creatures like Ratatoskr facilitate exchange, mirroring Viking trade networks that built prosperity through connection. This balance—order from Asgard, chaos from Jotunheim—fosters adaptability, a key cultural value for explorers facing unknown shores.

Ragnarök disrupts yet renews this equilibrium, with survivors like Lif and Lifthrasir repopulating from Yggdrasil’s seeds, emphasizing renewal through perseverance.

Rituals and Practices Centered on Yggdrasil

Vikings likely enacted tree-rites at sacred sites, offering to wells for wisdom. Modern Norse Pagans recreate this with Yggdrasil visualizations in blots, tracing the tree’s form to invoke balance. Rune-carvings on staves mimic its bark, used for divination to navigate wyrd.

Seasonal alignments—solstice fires for Muspelheim, winter offerings for Niflheim—reinforce cycles, promoting self-reliance in harmony with nature.

Cultural Values Embodied in Yggdrasil’s Lore

Yggdrasil encapsulates Viking virtues: courage in facing its beasts, honor in reciprocal offerings, hospitality through interconnected realms, self-reliance in enduring trials, and generosity in sharing its dew. These principles guided Viking life, from raids to homesteads, and continue to inspire ethical living.

Modern Engagement: Yggdrasil in Contemporary Norse Paganism

Today, Heathens meditate on Yggdrasil for grounding, perhaps journaling its realms to map personal growth. Crafts like tree-motif carvings or mead-brews honor its sustenance, while hikes in nature connect to Midgard’s vitality. This engagement revives Viking resilience, weaving ancient cosmology into modern paths of fulfillment.

Conclusion: The Eternal Ash and the Viking Spirit

Yggdrasil endures as the Norse cosmos’s beating heart, a testament to the Vikings’ profound insight into life’s interconnected dance. By honoring its realms and structure, modern Norse Pagans reclaim a heritage of strength, balance, and wonder, standing as steadfast as the World Tree itself amid the wyrd’s ever-turning wheel.

The Authentic Ancient Values of Vikings and Norse Paganism

Introduction

The cultural and spiritual values of the Viking and Norse Pagan societies are deeply rooted in a complex and multifaceted worldview that emphasizes a profound respect for nature, community, and the divine. These values are not merely abstract principles but are deeply embedded in the daily lives of the Norse people, influencing their actions, decisions, and interactions with one another. This essay explores the authentic ancient values of Viking and Norse Paganism, drawing from historical sources and anthropological studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of their cultural and spiritual significance.

Cosmology and the Nine Realms

At the heart of Norse cosmology lies Yggdrasil, the World Tree, which connects the nine realms of existence. These realms include Asgard (the home of the gods), Midgard (the world of humans), Jotunheim (the land of giants), Vanaheim (the realm of the Vanir gods), Alfheim (the land of the elves), Svartalfheim (the realm of the dwarves), Nidavellir (another realm of the dwarves), Muspelheim (the realm of fire), and Helheim (the underworld). This interconnectedness underscores the belief that all aspects of existence are interdependent and part of a larger cosmic order.

The Gods and Goddesses

Norse Paganism worships two main pantheons: the Aesir and the Vanir. The Aesir, gods of war and governance, include Odin, the All-Father and god of wisdom; Thor, the god of thunder and protection; and Tyr, the god of justice and law. The Vanir, deities of fertility and nature, include Freyr, the god of prosperity and fertility; Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility; and Njord, the god of the sea and wind. These gods and goddesses embody various aspects of life and nature, guiding adherents in their spiritual and daily lives.

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor worship is a central tenet of Norse Paganism. Practitioners seek guidance, protection, and wisdom from their forebears, often through rituals, storytelling, and maintaining physical reminders like altars or grave sites. This belief highlights the interconnectedness of past, present, and future generations, fostering a deep sense of continuity and belonging. Honoring ancestors reinforces family and community bonds, preserves cultural heritage, and provides moral examples for people to live by.

Ethical Living and Universal Ancient Values

Norse Paganism, like many ancient Pagan societies, emphasizes a set of ethical principles that promote communal harmony and personal integrity. These values are often derived from the Eddas and sagas, which provide insights into the moral and ethical beliefs of the ancient Norse people.

- Reciprocity: The concept of reciprocity is fundamental in Norse Paganism. This principle underscores the belief that communal harmony and personal prosperity depend on maintaining positive interactions with the divine and with one another. Rituals and offerings are often made to the gods and spirits to honor this relationship.

- Honor and Reputation: Honor is a central concept in Norse Paganism. Personal integrity and reputation impact one’s fate and standing within the community, mirrored by the deeds of heroic figures in Norse mythology.

- Hospitality: Hospitality is a key virtue in Norse Paganism, emphasizing the importance of welcoming guests and strangers with open arms. This practice fosters community bonds and reflects the broader ancient Pagan value of generosity and compassion.

- Courage and Valor: The Norse placed a high value on courage and valor, particularly in the face of adversity. This is evident in the stories of their gods and heroes, who often faced great challenges with bravery and determination.

- Respect for Nature: Norse Pagans maintain a profound relationship with the natural world, revering the spirits of land and water. This belief ensures that nature is treated with reverence and respect. Environmental stewardship and seasonal celebrations like Yule, Ostara, and Midsummer reflect this core belief.

- Community and Frith: The concept of frith, or peace and harmony within the community, is essential in Norse Paganism. This value emphasizes the importance of maintaining social order and mutual respect among community members.

- Wisdom and Knowledge: Wisdom is highly valued in Norse Paganism, as seen in the stories of Odin seeking knowledge and wisdom through various trials and sacrifices. The pursuit of knowledge and understanding is considered a noble endeavor.

- Resilience and Perseverance: The Norse valued resilience and perseverance, particularly in the face of adversity. This is evident in their sagas and myths, which often depict heroes overcoming great challenges through determination and steadfastness.

Rituals and Celebrations

Core rituals in Norse Paganism include Blót (sacrificial rites to honor the gods and spirits), Sumbel (a ritual of toasting, boasting, and oaths), and seasonal festivals. These rituals foster community and spiritual connection. For instance, during Yule, Norse Pagans celebrate the winter solstice with feasts, rituals, and community gatherings, often incorporating traditional Norse customs and symbolism.

Modern Relevance

In contemporary society, the core values of Norse Paganism resonate with many individuals seeking a clear, practical code of ethics. These values offer solutions to modern problems by providing guidance on how to live honorably and harmoniously with others. For instance, practicing hospitality and community frith can significantly improve social cohesion and mutual support in urban environments. Additionally, the pursuit of wisdom and knowledge can foster personal growth and understanding, encouraging individuals to thrive in their lives while maintaining a balanced approach to their interactions with the natural world and their community.

Conclusion

Norse Paganism is deeply rooted in a profound respect for nature, community, and honor, embodying principles that emphasize strength, courage, and wisdom. The core values, such as hospitality, truth, and perseverance, reflect a holistic worldview where personal integrity and loyalty to one’s kin are paramount. These values guide practitioners in their daily lives, reinforcing a sense of identity and purpose grounded in ancient traditions. The spiritual practices of Norse Paganism, including rituals and offerings to the gods, ancestors, and land spirits, further solidify these core principles. Embracing virtues like courage, wisdom, and respect for nature, Norse Paganism encourages a balanced life where the physical and spiritual realms are interwoven. These values are not static but are continuously interpreted and adapted by modern practitioners, ensuring their relevance in the contemporary world.

Concise Summary of the Key Stories From the Poetic Edda

Below is a concise summary of the key stories from the Poetic Edda, focusing on the main themes and events. The Poetic Edda is a collection of Old Norse poems dealing with mythology and heroics, divided into mythological and heroic lays.

Mythological Poems

- Völuspá (The Prophecy of the Seeress)

- A seeress narrates the creation of the world, the rise of the gods, and their eventual doom at Ragnarök.

- Key events: Ymir’s death, the creation of Midgard, the rise of humans, and the foretold destruction and rebirth of the world.

- Hávamál (Sayings of the High One)

- Odin shares wisdom, advice, and rules for living.

- Contains teachings on hospitality, friendship, love, and self-control.

- Includes the story of how Odin sacrificed himself to gain knowledge of the runes.

- Vafþrúðnismál (The Lay of Vafthrudnir)

- Odin competes in a wisdom contest with the giant Vafthrudnir.

- Odin wins by asking a question only he knows the answer to: what he whispered to Baldr before his death.

- Grímnismál (The Lay of Grímnir)

- Odin, disguised as Grímnir, reveals cosmic knowledge to young Agnarr while being tortured by King Geirröðr.

- Describes the worlds of Yggdrasil and the halls of the gods.

- Skírnismál (The Lay of Skírnir)

- Freyr sends his servant Skírnir to woo the giantess Gerðr on his behalf.

- Skírnir uses threats and magical coercion to secure Gerðr’s hand in marriage.

- Hárbarðsljóð (The Lay of Hárbarðr)

- Thor and a ferryman (disguised Odin) exchange insults as Thor tries to cross a river.

- The poem highlights their contrasting personalities.

- Hymiskviða (The Lay of Hymir)

- Thor and Tyr go on a quest to retrieve a giant cauldron from Hymir for brewing mead.

- Thor impresses by fishing the serpent Jörmungandr.

- Lokasenna (The Flyting of Loki)

- Loki insults the gods at a feast, revealing their flaws and past misdeeds.

- Ends with Loki fleeing but eventually being bound as punishment.

- Þrymskviða (The Lay of Thrym)

- Thor’s hammer Mjölnir is stolen by the giant Thrym, who demands Freyja as a bride.

- Thor, disguised as Freyja, retrieves his hammer by attending the wedding and slaying Thrym.

- Alvíssmál (The Lay of Alvís)

- Thor tricks the dwarf Alvíss, who wants to marry his daughter, by asking endless questions until sunrise, turning the dwarf to stone.

Heroic Poems

- Völundarkviða (The Lay of Völundr)

- The smith Völundr is captured by a king but takes revenge by killing the king’s sons and escaping after impregnating the king’s daughter.

- Helgakviða Hundingsbana I & II (The Lays of Helgi, Slayer of Hunding)

- The hero Helgi defeats Hunding and his kin, wins the love of the Valkyrie Sigrún, and faces tragedy as her family seeks revenge.

- Fáfnismál (The Lay of Fáfnir)

- Sigurd slays the dragon Fáfnir and gains wisdom by tasting its blood.

- Includes a conversation between Sigurd and the dying Fáfnir about life and fate.

- Reginsmál (The Lay of Regin)

- Regin, Fáfnir’s brother, manipulates Sigurd into killing Fáfnir to gain the dragon’s hoard.

- Sigurd later kills Regin upon realizing his treachery.

- Grípisspá (The Prophecy of Grípir)

- Sigurd consults his uncle Grípir, who foretells his heroic deeds and eventual betrayal by Brynhild.

- Sigrdrífumál (The Lay of Sigrdrífa)

- Sigurd awakens the Valkyrie Sigrdrífa (Brynhild) from a magical sleep, and she teaches him runes and wisdom.

- Atlakviða (The Lay of Atli)

- Gunnar and Högni are betrayed by Atli (Brynhild’s brother) and killed.

- Guðrún, Atli’s wife, takes revenge by killing their sons and serving them to Atli before killing him.

- Guðrúnarkviða I-III (The Lays of Guðrún)

- Guðrún mourns Sigurd’s death and faces trials in her life, including forced marriages and familial betrayal.

- The poems explore themes of grief, vengeance, and resilience.

- Oddrúnargrátr (The Lament of Oddrún)

- Oddrún, a lover of Gunnar, laments his tragic fate and her unfulfilled love for him.

- Hamðismál (The Lay of Hamðir)

- Guðrún’s sons avenge their sister Svanhild’s death by attacking King Jörmunrekkr but die in the attempt.

Themes of the Poetic Edda

- Cosmic Order & Fate: Stories often emphasize the inevitability of fate and the cyclical nature of time.

- Heroism & Tragedy: Heroes achieve greatness but face inevitable downfall due to their flaws or fate.

- Wisdom & Deception: Knowledge and cunning (often associated with Odin) play key roles in survival and power struggles.

- Vengeance & Loyalty: Family loyalty and revenge are recurring motives in the heroic lays.

This overview captures the essence of the Poetic Edda while providing a high-level understanding of its stories.

The Ephemeral Flame of the North: A Philosophical Odyssey through the Realm of the Vikings

In the depths of the boreal expanse, where the aurora borealis dances across the sky like a spectral bride, there existed a people whose essence was as elusive as the wind and as unforgiving as the winter’s grasp. The Vikings, those enigmatic sons of Odin, left behind a legacy that is at once a testament to their unyielding spirit and a mystery that beckons us to delve into the labyrinthine corridors of their culture. This essay is an attempt to navigate the philosophical underpinnings of Viking society, to unravel the threads of their worldview, and to illuminate the esoteric dimensions of their existence.

At the heart of Viking philosophy lies the concept of wyrd, a term that defies translation but approximates to fate or destiny. Wyrd is not merely a predetermined course of events but an active, dynamic force that weaves the tapestry of existence. It is the Vikings’ acknowledgment of the intricate web of causality that binds all things, a recognition that every action, every decision, sends ripples through the fabric of reality. This understanding of wyrd as an omnipresent, omniscient force underscores the Viking belief in a universe governed by laws both natural and divine.

The Vikings’ relationship with nature was not one of domination but of symbiosis. They saw themselves as part of the natural world, not apart from it. Their gods and goddesses were not distant, unapproachable deities but beings intimately connected with the land, the sea, and the sky. Thor, the god of thunder, wielded his hammer Mjolnir not just as a weapon but as a tool to maintain the balance of nature, to ensure the cycle of seasons and the fertility of the earth. Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility, was also the goddess of war and death, symbolizing the Vikings’ acceptance of life’s dualities.

Their cosmology, as depicted in the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, presents a universe born from chaos, where the primordial giant Ymir and the great serpent Jörmungandr embody the eternal struggle between order and disorder. The Vikings’ world was one of contrasts: light and darkness, fire and ice, creation and destruction. This dichotomy is reflected in their concept of honor, which was not merely a personal virtue but a communal one, tied to the reputation of the family and the clan. Honor was the thread that held society together, the glue that bonded warriors in battle and the standard by which one’s worth was measured.

The Vikings were a people of action, their philosophy manifest in their deeds rather than in abstract speculation. Theirs was a world of doing, where one’s character was revealed through actions, not words. The berserker, that frenzied warrior who fought with a fury that seemed almost divine, was the embodiment of the Viking ideal of courage and strength. Yet, this ferocity was balanced by a deep sense of loyalty and hospitality, virtues that were considered essential to the Viking way of life.

Their art and literature, as preserved in the runestones and the sagas, speak of a people deeply concerned with the human condition. The Vikings pondered the mysteries of life and death, of fate and free will, in stories that were both entertainments and teachings. The Völuspá, the first poem of the Poetic Edda, is a prophetic vision of the end of the world, a reminder of the transience of all things and the inevitability of change.

In their funerary rites, the Vikings demonstrated a profound respect for the dead, believing that the soul continued its journey into the afterlife. The ship burials, with their treasures and provisions for the journey, were not merely displays of wealth but expressions of the Vikings’ belief in an afterlife that mirrored this one. Valhalla, the great hall of the slain, where warriors fought by day and feasted by night, was the ultimate destination for those who died in battle, a place where honor and glory were eternal.

The Viking worldview was not static; it evolved over time, influenced by their encounters with other cultures. Their conversion to Christianity marked a significant shift, as they adapted the new faith to their existing beliefs, creating a unique synthesis that preserved much of their pagan heritage. This blending of traditions is a testament to the Vikings’ pragmatic approach to religion, their recognition that truth can be found in many forms.

As we delve into the philosophical dimensions of Viking culture, we are reminded of the impermanence of all things. The Vikings, with their keen awareness of mortality, lived in the present, cherishing each moment as a gift. Theirs was a philosophy of carpe diem, of seizing the day, for in the words of the Viking proverb, “Cattle die, kinsmen die, you yourself will die, but one thing I know that never dies: the judgment of a dead man’s deeds.”

In the end, the Vikings leave us with more questions than answers, their culture a labyrinth of contradictions and paradoxes. They were warriors and poets, pagans and Christians, individualists and communalists. Yet, it is in these contradictions that we find the essence of their philosophy, a worldview that embraced complexity and ambiguity. The Vikings remind us that life is a journey, not a destination, and that our deeds, not our words, are the measure of our character.

As the flame of the Viking Age flickers out, leaving behind only embers of memory, we are left to ponder the wisdom of their way of life. In a world that values certainty and clarity, the Vikings offer us a different path, one that celebrates ambiguity and uncertainty. Their philosophy is a reminder that truth is multifaceted, that reality is complex, and that the human experience is a tapestry woven from countless threads.

In the silence of the boreal night, under the watchful gaze of the aurora borealis, we can still hear the whispers of the Vikings, their voices carried on the wind. They speak to us of a world that was, of a people who lived and loved and laughed and fought. They remind us that we are not alone in this vast and mysterious universe, that we are part of a larger whole, connected to all that has been and all that will be.

And so, we return to the beginning, to the concept of wyrd, that mysterious force that weaves the tapestry of existence. The Vikings understood that our lives are not our own, that we are part of a larger narrative that unfolds with each passing moment. Their philosophy is a call to embrace this uncertainty, to find meaning in the midst of chaos, and to live each day with purpose and passion.

In the end, the Vikings teach us that life is a journey, not a destination. It is a path that winds through the mountains and valleys of existence, a road that is fraught with danger and filled with wonder. And it is on this journey, in the midst of uncertainty and ambiguity, that we find the true meaning of the Viking way of life.

The ancient goddess Nehalennia

Nehalennia is a very ancient Vanic goddess. She is goddess of the ocean. She is related to hounds, trade, the sea, ships, and the harvest of the sea itself. She rules over passage from one state to another, such as the transitions from living to death (or my theory is the other way around too), and any journeys by water. She is an ancestor goddess of Njord, Freyja, and Freya. Her nature seems to be calming, gentle and providing, yet wild and untamed, in many ways like the character of the sea itself. She is seen to have very water like appearance. Some see her as very beautiful, with wide bright young eyes like a young girls, a perfect and lean figure, and wearing a hound necklace, being topless and wearing a very tiny mini skirt, and wearing a fishing net as a shawl. Her color is a blue green like the sea. I feel her runic energy for sure is laguz in a big way! Alternate spellings of her name are Nehelennia, and Nehalenni.

Nehalennia is a very ancient Vanic goddess. She is goddess of the ocean. She is related to hounds, trade, the sea, ships, and the harvest of the sea itself. She rules over passage from one state to another, such as the transitions from living to death (or my theory is the other way around too), and any journeys by water. She is an ancestor goddess of Njord, Freyja, and Freya. Her nature seems to be calming, gentle and providing, yet wild and untamed, in many ways like the character of the sea itself. She is seen to have very water like appearance. Some see her as very beautiful, with wide bright young eyes like a young girls, a perfect and lean figure, and wearing a hound necklace, being topless and wearing a very tiny mini skirt, and wearing a fishing net as a shawl. Her color is a blue green like the sea. I feel her runic energy for sure is laguz in a big way! Alternate spellings of her name are Nehelennia, and Nehalenni.

Some consider her a goddess of the dead, but I feel that isn’t exactly correct. She isn’t a Goddess that comes to claim the dead, but more one that helps them to safely make their journey to that realm. She basically rules safe passage from one place to another (either places being earthly places or even places as in states of being as in travel from the world of the living to world of the dead). This is more of a protecting and nurturing thing. Not harsh like for example Hel can be at times. Basically the historical offerings to her that have been found, they seem to have found were ones given in thanks for sailors making safe passage. Travel in general is associated in movement from one realm to another. This is connected with the rune laguz. This seems to be her energies. She is very connected to the goddess and female mysteries of helping beings pass from one state to another. Since women are the ones who give birth they rule over this aiding of beings coming from one realm to the other. Birth is a transition from the spiritual realm to the physical realm, in the same way birth is a transition from the physical realm to the spiritual realm. What is interesting also about birth and about the womb is it is a realm filled with water. This is very connected to the mysteries of wells or caldrons in the Norse cosmology. There are three important wells, and it is considered that wyrd (the Norse concept of fate or karma) for all beings flows through these wells. It is of course water that flows through wells so it seems wyrd and water are very connected. Since Nehalennia is a goddess that can be seen as the personification of water itself, it only makes sense that she rules over this mystery of the passage of wyrd or the passage from one state to another or even journeys or movement in general. Another rune connected with this mystery is perthro, but perthro may be considered the captured state of the flow of water in a sudden given moment. Yet Nehalennia seems to be more the open oceans, waters freely flowing without restriction, thus she is more related to laguz, not really to the parts of this process connected to perthro. Perthro is more the well structure itself, the vagina, laguz is more the water contained in it. A vagina is of course a very wet comforting place. ;) These mysteries are very Vanic in nature, since the Vanir are connected to both sexuality and to water and ships.

The drawing I have of Nehalennia is made by Amarina and used with her permission.

More about Nehalennia:

Amarina’s experience of Nehalennia.

Another very good post Amarina wrote about her impressions of Nahalennia, and the Vanir as a whole.

Info based on spiritual experiences of Nehalennia on Amarina’s blog.

Info on Hehalennia from livius.org.

She is written about in Our Troth Volume 1, pages 394-395.

She is also in Exploring the Northern Tradition, page 118.

An invocation to Nehalennia:

Hail Nehalennia! Beautiful goddess of the hounds, trade, and the sea! Lost lady of the Vanir! Ancestor of Njord, Freyja, and Freyr!

Very insightful video on elves…

The elves and related being are a very important part of Heathenism. They represent a large variety of beings. The Norse term used for spiritual beings in general is wights.