Grand Solitary Ritual for Winter’s Nights (Vetrnætr)

Grand Solitary Ritual for Winter’s Nights (Vetrnætr)

By Astrid Freyjasdottir of the Heathen Third Path

Introduction

Winter’s Nights, celebrated around mid-to-late October, marks the shift from harvest to winter in the Norse Pagan calendar. It is a time to honor the ancestors, the land, the Vanir (such as Freyja and Freyr), and the spirits who sustain us through the dark months.

This grand solitary ritual is designed for the Heathen Third Path—rooted in tradition, inclusive, and practical, blending reverence with personal reflection. It takes 30–45 minutes and may be done indoors or outdoors, in city or wild places. It is trauma-aware, adaptable, and meant to leave you feeling connected, steady, and warmed by the sacred.

Purpose

To honor the turning of seasons, give thanks for the harvest, seek blessings for the winter ahead, and deepen your bond with ancestors, land spirits, and the Gods and Goddesses. This ritual balances celebration and introspection, inviting abundance, protection, and wisdom.

What You’ll Need

- Altar Space – A table, flat stone, or cleared ground. Decorate with leaves, acorns, apples, pinecones.

- Candle or Fire – A large white or gold candle, or a fire-safe bowl flame (substitute natural items if fire isn’t possible).

- Offerings – A cup of mead, cider, or juice; a small bowl of grain, bread, or nuts; an ancestor token (photo, heirloom, written name).

- Runes – A rune set, or slips of paper with runes such as Jera, Ehwaz, Perthro.

- Notebook & Pen – For journaling insights and intentions.

- Drum or Rattle (optional) – Or simply clap or tap for rhythm.

- Blanket or Shawl – To wrap yourself in warmth, symbolizing winter’s embrace.

- Small Bowl of Water – For cleansing and blessing.

Preparation

- Choose a quiet evening during Winter’s Nights (traditionally October 14–20, but align with your local season).

- Outdoors: find a safe spot like a backyard, park, or forest edge.

- Indoors: clear a quiet space.

- Dress warmly, perhaps in earth tones or a scarf that feels sacred.

- Breathe deeply. Whisper to yourself:

“I step into the sacred tide of Winter’s Nights, held by the land, seen by the ancestors, blessed by the Gods.”

Ritual Steps

1. Cleanse and Center

- Dip fingers into the water. Touch forehead, heart, and hands.

- Say: “By water’s flow, I am clear. By earth’s strength, I am steady.”

- Breathe deeply three times. Visualize roots growing from your feet, grounding you into the land.

2. Set the Altar

- Place the candle/fire in the center.

- Arrange offerings and ancestor token.

- Circle with seasonal items.

- Say: “This is my hearth, my hall, my sacred grove. Here, the land, ancestors, and Gods meet.”

- Light the candle/fire.

- Say: “Fire of life, light of kin, shine through the dark, guide me within.”

3. Call to the Sacred

Raise arms or open palms. Speak:

“Hail to the land, the frost-kissed earth, the roots that hold.

Hail to the ancestors, mothers and fathers, whose stories weave my own.

Hail to the Vanir—Freyja, Freyr, Njord—who bless the harvest and hearth.

Hail to the Aesir—Frigg, who guards the home; Thor, who shields the weary.

Hail to the spirits of this place, the trees, the stones, the hidden ones.

I stand in Winter’s Nights, open to your wisdom, grateful for your gifts.”

(Pause. Feel the presence of those you have called.)

4. Offerings for Gratitude

- Sip the mead/cider. Pour some out. Say: “This I share with the land, the ancestors, and the Gods, in thanks for the harvest and the strength to come.”

- Scatter grain/nuts. Say: “This I give for abundance, for the seeds that sleep and rise again.”

- Place the ancestor item on the altar. Say: “To my kin, known and unknown, I offer my love and memory. Guide me through the winter.”

5. Rune Reading for the Season

- Ask: “What wisdom will carry me through winter?”

- Draw three runes:

- Past – What have I harvested this year?

- Present – What anchors me now?

- Future – What should I carry into the dark months?

- Past – What have I harvested this year?

- Reflect and journal. Say: “Norns, weavers of fate, let these runes guide my path.”

6. Chant or Song for Connection

Begin rhythm with drum, rattle, clapping, or foot-tapping. Chant three times:

“Frost on the field, fire in the heart,

Ancestors call, we never part.

Freyja’s warmth, Freyr’s grain,

Through winter’s dark, we rise again.”

(Or hum/speak a single line, e.g., “I walk with the land, kin, and Gods.”)

7. Set an Intention for Winter

- Wrap yourself in the blanket/shawl.

- Say: “As the nights grow long, I carry light within. I honor the past, stand in the present, and trust the future.”

- Write one intention for the season. Place the notebook on the altar.

8. Close with Gratitude

Gaze at the candle. Speak:

“Thank you, land, for your enduring gifts.

Thank you, ancestors, for your unending love.

Thank you, Gods and Goddesses, for your light in the dark.

Thank you, spirits of this place, for sharing this moment.”

Extinguish the flame. Keep ancestor item or notebook near.

Tips for a Meaningful Ritual

- Adapt to Your Space – Open a window indoors or honor stars and wind outdoors.

- Trauma-Aware – Simplify if overwhelmed. The Gods and ancestors value presence, not perfection.

- Make It Personal – Add your own songs, poems, or heritage foods.

- Local Connection – Honor a nearby tree, stone, or bird.

- Aftercare – Journal, sip tea, let emotions flow freely.

- Extend the Sabbat – Offer crumbs or drops of water in days following.

Why This Ritual Matters

Winter’s Nights is a threshold—a time to honor what has been, prepare for what will be, and weave yourself into the sacred cycle of land, kin, and divine.

This ritual roots you in the Heathen Third Path’s values: inclusivity, continuity, and kindness, free from dogma or extremes. It reminds you that even in solitude, you are never alone—the ancestors whisper in your blood, the Gods walk with your courage, and the land holds you steady.

May this ritual wrap you in the warmth of Winter’s Nights, love, and carry you through the season with strength and joy.

Reclaiming the Sacred: How the Concept of “Religion” Became a Tool of Control

When people in the modern world speak of religion, they often think of rigid doctrines, centralized institutions, rules, and hierarchies. This view—so commonly accepted that it’s rarely questioned—does not arise from a universal truth about all spiritual systems. Rather, it reflects the structure and influence of a particular family of religions: the Abrahamic traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In contrast, most other spiritual paths around the world—whether Pagan, Indigenous, or Eastern—developed in vastly different cultural environments. These systems were rarely dogmatic or authoritarian. Instead, they were integrated into everyday life, fluid, and rooted in local traditions, seasons, and personal or communal experiences. To understand how we arrived at this dominant idea of religion as rigid and controlling, we must look into the cultural foundations of these traditions.

The Abrahamic Model of Religion: A Historical Product

Judaism, Christianity, and Islam emerged in regions where survival and identity were tightly bound to communal order. Each evolved amid political instability, conquest, and foreign occupation. Over time, they developed strong systems of law, sacred texts, and theological boundaries. They also promoted the idea of a single correct path, often enforced with religious and political authority combined.

Christianity in particular, after merging with the Roman Empire under Emperor Constantine, absorbed the empire’s love of structure, law, and centralized control. Early church councils mimicked Roman senates. Heresy became equivalent to political treason. Over time, Christianity became not just a spiritual path, but a mechanism for enforcing cultural uniformity throughout Europe and beyond.

Islam too developed within a tribal, pastoralist society in Arabia, where strong communal codes were essential for survival. The resulting emphasis on submission to divine law, collective unity, and a comprehensive social code was essential in that environment—and shaped Islam’s character profoundly.

The Cultural Roots of Control

These historical pressures meant that the Abrahamic religions often served more than spiritual needs—they became tools for managing society. Belief systems were not just about the divine, but about authority, allegiance, and the governance of human behavior. When these traditions spread through conquest, colonization, or missionary work, they brought not just new gods, but new ideas of what religion is and how it should function.

In many ways, Christianity became an extension of Roman imperial ideals, continuing the obsession with order, loyalty, and hierarchy—now sanctified by divine authority. The focus shifted from personal or communal sacred experience to obedience, orthodoxy, and centralized religious control.

The Misapplication of the Word “Religion”

Before these models dominated global consciousness, most cultures had no word equivalent to “religion” as we use it today. Spirituality was not separated from daily life—it was how people lived in rhythm with the world, the gods, their ancestors, and the land.

For example:

- Norse Paganism had no “church” or creed—just líf (life), bound by frith (sacred peace), ritual, and kinship with the gods and spirits.

- Hindu dharma encompasses duty, law, and spiritual path, but it’s not “religion” in the Western sense—it is a way of life tied to nature, cosmology, and personal growth.

- Shinto has no sacred book, no founder, and no claim to exclusive truth—just reverence for nature, ancestors, and sacred purity.

In Indigenous traditions, whether in Africa, the Americas, Australia, or Siberia, the spiritual world is lived, not preached. There is no conversion, no centralized doctrine, no rigid hierarchy—only the ongoing relationship between people and the sacred.

A Broader Perspective on Spirituality

The idea that “religion is inherently oppressive” only makes sense when looking through the lens of the Abrahamic traditions—especially after their fusion with empire and law. When that same label is applied to non-Abrahamic paths, it becomes a distortion.

Spirituality, in its original form for most cultures, was not a set of beliefs to enforce. It was a way of belonging to the world. It was not about control, but connection—through ritual, myth, seasonal cycles, personal experience, and respect for mystery.

Conclusion: The Return of the Living Path

As more people turn to Earth-based paths, Pagan revivals, animistic traditions, and Eastern philosophies, we are seeing a rebirth of something ancient. A sacred way of living that doesn’t rely on centralized authority or control. A path that recognizes that the divine is not found in rigid rules, but in rivers, stars, dreams, and the bones of the land.

By understanding the cultural origins of our modern religious frameworks, we can stop applying the same expectations—and criticisms—to traditions that were never meant to fit into that mold.

Religion, as most people think of it today, is not universal. It is a construct born from a specific historical context, often tied to conquest and control. But the sacred is much older than that—and far more free.

The Worth of Witches, Wizards, and Gothar in Norse Paganism: Strength of the Inner World

The ancient Norse understood that strength comes in many forms. While warriors fought with axe and shield, those who walked the path of the mind—witches, wizards, and Gothar—held power that shaped fate itself. Their worth was not bound by physical might, nor by the limitations of the body, but by the vastness of their minds, the depth of their wisdom, and their connection to the unseen forces that weave the fabric of reality.

For those with a strong intellect, an instinct for the unseen, and a natural pull toward the inner realms, this path is open. And for those who carry physical disabilities or even mental disabilities, their worth in this role is often even greater. It is not muscle that or social skillls that determines one’s ability to wield magic, interpret the runes, commune with spirits, or serve as a spiritual guide—it is will, wisdom, and the strength of the unseen mind.

The Role of the Inner World in Norse Culture

In Viking and Norse Pagan society, there was a deep respect for those who wielded knowledge of the hidden world. Seiðr practitioners (Norse Witches), Rune Masters (Norse Wizards), spirit-workers, and Gothar (priests, priestesses, and spiritual leaders) were not warriors in the traditional sense, yet they held power that even the greatest warriors sought. Odin himself, the Allfather, was not the strongest in battle, yet he ruled over the gods through wisdom, cunning, and mastery of the unseen.

To walk the path of magic, foresight, and spiritual guidance required:

- A sharp and disciplined mind – Knowledge of runes, omens, and the workings of fate.

- The ability to connect with unseen forces – Speaking with the gods, spirits, and ancestors.

- A willingness to walk alone at times – The path of wisdom is not always understood by others.

For those whose bodies do not grant them the ability to lift a sword, or social skills to fit into a warrior hierarchy, their minds often sharpen instead, cutting deeper than any blade. Physical and social limitations push the mind inward, strengthening focus, intuition, and mastery over thought. Those who cannot walk far in the physical or social world often walk further in the spiritual one.

Physical and Mental Disability as a Gateway to Inner Strength

Many people with physical or mental disabilities are naturally inclined toward paths of the mind. When the body or social skills does not allow one to chase after fleeting external pursuits, the mind turns inward. This is not weakness—it is a different kind of strength, one that the foolish often fail to see.

- A Mind Unburdened by the Distractions of War

- A warrior focuses on survival and combat, often missing the deeper mysteries of the world.

- Those who focus on wisdom and magic do not need the distractions of battle to find their worth.

- Forced Adaptation Leads to Mastery of Thought

- When the body or social skills struggles, the mind sharpens to compensate.

- Deep introspection, visualization, and mental clarity become stronger skills.

- Greater Connection to the Otherworldly

- Those less bound to the physical or worldly pursuits often find it easier to commune with spirits and gods.

- Many seers, oracles, and shamans in various cultures had physical or mental disabilities that deepened their connection to the unseen.

- Resilience Creates a Powerful Will

- Facing challenges in the physical or social world breeds an indomitable spirit.

- This willpower makes one a force to be reckoned with in matters of magic, wisdom, and fate.

The weak-willed cannot hold these roles. But those who see through the illusions of physical power, and instead build their mind and spirit, become leaders in their own right.

The High Status of the Gothar, Witches, and Wizards in Norse Society

The Gothar (priests, priestesses, and spiritual leaders), seiðr practitioners (Norse Witches), and Rune Masters (Norse Wizards) were highly valued in Norse society. Their status was equal to, or in some cases greater than, warriors and kings because they were the ones who dictated the flow of fate. A warrior may be strong in battle, but without the guidance of the wise, their strength is directionless.

- Gothar were the spiritual leaders of their communities. They led rituals, maintained law and tradition, and served as the voice of the gods among the people.

- Seiðr practitioners (those who practiced magic, like Odin and Freyja) were feared and respected. They shaped fate, wove spells, and guided people through visions and divination.

- Rune masters were scholars and wielders of written power. They carried knowledge that could heal, curse, protect, and control the forces of nature.

The warrior who ignores wisdom fights blindly. The strong who lack guidance fall into ruin. This is why those who command the unseen world were vital to Viking society and remain essential in modern Norse Paganism today.

Breaking Free from Insecurity and Stupidity

Many who walk this path hesitate because of insecurity, because of the false belief that they are somehow “lesser” if they cannot wield a sword or stand among the physically strong. This is a lie told by those who do not understand Norse culture.

In the modern world, too many misunderstand the values of the old ways. They think strength only comes from physical power, but true strength is in knowing oneself, mastering one’s path, and giving back to the community. Those who do not understand this are fools—and their opinions hold no weight.

- Your worth is not given—it is claimed.

- Your strength is in your mind, and no one can take that from you.

- You have talents, gifts, and a path meant for you. You only need to be brave enough to walk it.

- Worldly status, and money wealth only matter to those with the Jarl role in Viking society.

The only obstacles in life are those we create for ourselves through insecurity and fear. Physical hardship does not weaken you—fear of stepping into your own worth does.

Claiming Your Place in Norse Paganism

To walk the path of wisdom, one must own their identity with confidence. If you are drawn to the inner world, if your mind burns with curiosity, if you feel the pull of the gods, spirits, and the unseen—then this is your path.

- Learn the runes, study their meanings, and practice them with intent.

- Train your mind daily—meditate, visualize, and sharpen your thoughts.

- Honor the old ways through ritual, reading, and connecting with others who share your path.

- Surround yourself with those who see your worth, and cast aside those too blind to understand.

You are not weak. You are not lesser. You are needed. The world will always need those who walk the unseen roads, who wield the wisdom of the ancients, and who guide others with knowledge and power.

Stand tall. Walk your path. Claim your place.

By the will of Odin, the wisdom of Freyja, and the strength of Thor, those who embrace their worth will stand unshaken.

🔥 Thus it is spoken. Thus it shall be. 🔥

The Nine Noble Virtues: Reflecting Christian Puritan Values More Than Authentic Ancient Viking Norse Pagan Values

Introduction

The Nine Noble Virtues (NNV) have become a cornerstone of modern Heathenry and Norse Paganism, often presented as a distillation of ancient Viking and Norse values. However, a closer examination reveals that these virtues are more reflective of Christian Puritan values than they are of the authentic ancient Viking and Norse Pagan values. This essay explores the origins and nature of the Nine Noble Virtues, comparing them to the ethical and moral principles found in both ancient Norse literature and Christian Puritanism.

Origins of the Nine Noble Virtues

The Nine Noble Virtues were first formalized by the Odinic Rite, a modern pagan organization, in the 20th century. They were developed as a way to articulate values drawn from the Old Norse sagas, Eddas, and other historical texts. The virtues include:

- Courage

- Truth

- Honor

- Fidelity

- Discipline

- Hospitality

- Industriousness

- Self-Reliance

- Perseverance

While these virtues are inspired by themes found in ancient Norse literature, they are not historical in origin. Instead, they reflect a modern interpretation of ancient texts, often influenced by contemporary ethical frameworks.

Ancient Norse Values

The ethical and moral principles of ancient Norse society were deeply intertwined with their cosmology, mythology, and daily practices. Key values included:

- Reciprocity: The belief in maintaining balanced relationships with the gods, spirits, and other humans through rituals and offerings.

- Honor and Reputation: Personal integrity and reputation were highly valued, impacting one’s standing within the community.

- Hospitality: Welcoming guests and strangers with generosity and kindness was a sacred duty, essential for communal harmony.

- Courage and Valor: Facing challenges with bravery and determination was a central theme in Norse mythology.

- Respect for Nature: Reverence for the natural world and its spirits was integral to Norse Paganism.

- Community and Frith: Maintaining peace and harmony within the community was essential.

- Wisdom and Knowledge: The pursuit of wisdom, as exemplified by Odin’s quests for knowledge, was highly valued.

- Resilience and Perseverance: Overcoming adversity through determination was a common theme in Norse sagas.

Comparison with Christian Puritan Values

Christian Puritanism, which emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries, emphasized a strict moral code aimed at achieving personal and societal purity. Key Puritan values included:

- Discipline: Strict self-control and adherence to moral and religious principles.

- Industriousness: Hard work and productivity as a means of achieving prosperity and fulfilling one’s duties.

- Self-Reliance: Independence and self-sufficiency, minimizing reliance on others.

- Truth and Honesty: Integrity and honesty in all dealings.

- Perseverance: Endurance and persistence in the face of challenges.

Analysis

The Nine Noble Virtues share significant overlap with Christian Puritan values, particularly in their emphasis on discipline, industriousness, self-reliance, truth, and perseverance. These values reflect a modern ethical framework that aligns more closely with Puritan ideals than with the authentic ancient Norse values.

For instance, the ancient Norse placed a high value on communal bonds and mutual aid, as seen in their emphasis on hospitality and frith. In contrast, the Nine Noble Virtues emphasize individual self-reliance, which is more reflective of Puritan ideals. Similarly, the ancient Norse valued wisdom and knowledge as means of achieving personal and communal harmony, while the Nine Noble Virtues focus more on individual perseverance and industriousness.

Conclusion

The Nine Noble Virtues, while inspired by themes from ancient Norse literature, are more reflective of Christian Puritan values than they are of authentic ancient Viking and Norse Pagan values. The emphasis on discipline, industriousness, self-reliance, and perseverance aligns more closely with Puritan ethics than with the communal, reciprocal, and nature-oriented values of ancient Norse society. This modern interpretation of ancient values offers a unique perspective on Norse Paganism but should be understood within its historical and cultural context.

The Authentic Ancient Values of Vikings and Norse Paganism

Introduction

The cultural and spiritual values of the Viking and Norse Pagan societies are deeply rooted in a complex and multifaceted worldview that emphasizes a profound respect for nature, community, and the divine. These values are not merely abstract principles but are deeply embedded in the daily lives of the Norse people, influencing their actions, decisions, and interactions with one another. This essay explores the authentic ancient values of Viking and Norse Paganism, drawing from historical sources and anthropological studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of their cultural and spiritual significance.

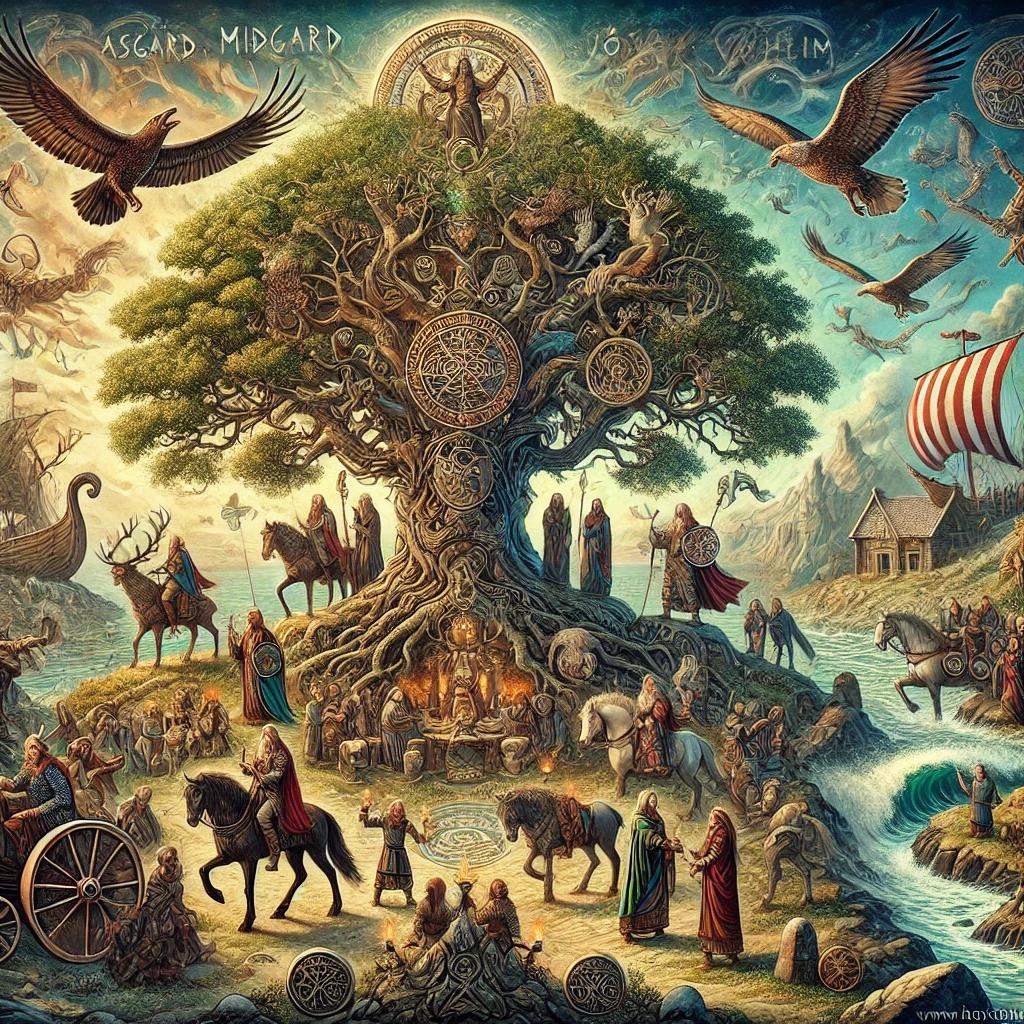

Cosmology and the Nine Realms

At the heart of Norse cosmology lies Yggdrasil, the World Tree, which connects the nine realms of existence. These realms include Asgard (the home of the gods), Midgard (the world of humans), Jotunheim (the land of giants), Vanaheim (the realm of the Vanir gods), Alfheim (the land of the elves), Svartalfheim (the realm of the dwarves), Nidavellir (another realm of the dwarves), Muspelheim (the realm of fire), and Helheim (the underworld). This interconnectedness underscores the belief that all aspects of existence are interdependent and part of a larger cosmic order.

The Gods and Goddesses

Norse Paganism worships two main pantheons: the Aesir and the Vanir. The Aesir, gods of war and governance, include Odin, the All-Father and god of wisdom; Thor, the god of thunder and protection; and Tyr, the god of justice and law. The Vanir, deities of fertility and nature, include Freyr, the god of prosperity and fertility; Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility; and Njord, the god of the sea and wind. These gods and goddesses embody various aspects of life and nature, guiding adherents in their spiritual and daily lives.

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor worship is a central tenet of Norse Paganism. Practitioners seek guidance, protection, and wisdom from their forebears, often through rituals, storytelling, and maintaining physical reminders like altars or grave sites. This belief highlights the interconnectedness of past, present, and future generations, fostering a deep sense of continuity and belonging. Honoring ancestors reinforces family and community bonds, preserves cultural heritage, and provides moral examples for people to live by.

Ethical Living and Universal Ancient Values

Norse Paganism, like many ancient Pagan societies, emphasizes a set of ethical principles that promote communal harmony and personal integrity. These values are often derived from the Eddas and sagas, which provide insights into the moral and ethical beliefs of the ancient Norse people.

- Reciprocity: The concept of reciprocity is fundamental in Norse Paganism. This principle underscores the belief that communal harmony and personal prosperity depend on maintaining positive interactions with the divine and with one another. Rituals and offerings are often made to the gods and spirits to honor this relationship.

- Honor and Reputation: Honor is a central concept in Norse Paganism. Personal integrity and reputation impact one’s fate and standing within the community, mirrored by the deeds of heroic figures in Norse mythology.

- Hospitality: Hospitality is a key virtue in Norse Paganism, emphasizing the importance of welcoming guests and strangers with open arms. This practice fosters community bonds and reflects the broader ancient Pagan value of generosity and compassion.

- Courage and Valor: The Norse placed a high value on courage and valor, particularly in the face of adversity. This is evident in the stories of their gods and heroes, who often faced great challenges with bravery and determination.

- Respect for Nature: Norse Pagans maintain a profound relationship with the natural world, revering the spirits of land and water. This belief ensures that nature is treated with reverence and respect. Environmental stewardship and seasonal celebrations like Yule, Ostara, and Midsummer reflect this core belief.

- Community and Frith: The concept of frith, or peace and harmony within the community, is essential in Norse Paganism. This value emphasizes the importance of maintaining social order and mutual respect among community members.

- Wisdom and Knowledge: Wisdom is highly valued in Norse Paganism, as seen in the stories of Odin seeking knowledge and wisdom through various trials and sacrifices. The pursuit of knowledge and understanding is considered a noble endeavor.

- Resilience and Perseverance: The Norse valued resilience and perseverance, particularly in the face of adversity. This is evident in their sagas and myths, which often depict heroes overcoming great challenges through determination and steadfastness.

Rituals and Celebrations

Core rituals in Norse Paganism include Blót (sacrificial rites to honor the gods and spirits), Sumbel (a ritual of toasting, boasting, and oaths), and seasonal festivals. These rituals foster community and spiritual connection. For instance, during Yule, Norse Pagans celebrate the winter solstice with feasts, rituals, and community gatherings, often incorporating traditional Norse customs and symbolism.

Modern Relevance

In contemporary society, the core values of Norse Paganism resonate with many individuals seeking a clear, practical code of ethics. These values offer solutions to modern problems by providing guidance on how to live honorably and harmoniously with others. For instance, practicing hospitality and community frith can significantly improve social cohesion and mutual support in urban environments. Additionally, the pursuit of wisdom and knowledge can foster personal growth and understanding, encouraging individuals to thrive in their lives while maintaining a balanced approach to their interactions with the natural world and their community.

Conclusion

Norse Paganism is deeply rooted in a profound respect for nature, community, and honor, embodying principles that emphasize strength, courage, and wisdom. The core values, such as hospitality, truth, and perseverance, reflect a holistic worldview where personal integrity and loyalty to one’s kin are paramount. These values guide practitioners in their daily lives, reinforcing a sense of identity and purpose grounded in ancient traditions. The spiritual practices of Norse Paganism, including rituals and offerings to the gods, ancestors, and land spirits, further solidify these core principles. Embracing virtues like courage, wisdom, and respect for nature, Norse Paganism encourages a balanced life where the physical and spiritual realms are interwoven. These values are not static but are continuously interpreted and adapted by modern practitioners, ensuring their relevance in the contemporary world.

Unyielding Honor: The Viking Demand for Truth and Reliability

From a traditional Norse or “Viking” standpoint, reliability and honesty were indeed of paramount importance. While popular culture often focuses on the Vikings as raiders and explorers, Norse society—like most tight-knit communities—relied on mutual trust and clear expectations to function smoothly. Below are some cultural and historical insights that underline why saying one thing and doing another would be seen in an extremely negative light in a Viking context:

1. Honor and Reputation (Drengskapr)

- Key Norse Concept: Among the Vikings, a person’s honor (drengskapr) was intimately tied to their reputation in the community. If you broke your word, it wasn’t just a private matter; it could tarnish your name, impact alliances, and diminish your standing.

- Long-Term Consequences: In small Norse communities, once your reputation was damaged, it was difficult to recover. Oath-breakers or those who spoke untruths could become social outcasts, losing the protection and support of the community.

2. The Weight of Oaths

- Binding Agreements: Oaths (especially formal ones) were taken very seriously in Viking society—sometimes witnessed by a god like Odin or by representatives of a community.

- Legal and Social Ties: Disputes, deals, and even friendships (fostering or blood-brotherhood) were cemented by solemn pledges. Reneging on these vows was seen as not only dishonorable but also dangerous—potentially sparking feuds.

3. Saga Literature Examples

- Condemnation of Betrayal: In the sagas, characters who violate their word or betray someone’s trust often become tragic figures, sometimes facing harsh retribution or living in shame.

- Enduring Legacy: These stories served as cultural touchstones. They taught that deceit could lead to broken alliances, vengeance, and even the downfall of entire families or communities.

4. Reciprocal Responsibility

- Social Glue: Reliability and honesty weren’t just individual virtues; they were necessary for the entire Norse social fabric. A chieftain or jarl who deceived his people lost loyalty, just as a free farmer (bondi) who betrayed a neighbor could lose essential support.

- Collective Security: In a harsh environment, you depended on your neighbors and allies for survival—especially during winter, or when out at sea. Flaking out or double-crossing someone jeopardized everyone’s well-being.

5. Modern “Viking” Values

- Neo-Pagan & Modern Interpretations: Many individuals today who follow a Norse-inspired path embrace those traditional tenets of honesty, loyalty, and respect because they resonate with the spirit of the sagas.

- Personal Integrity: Acting consistently and honoring commitments is viewed not just as a personal virtue but as a way to honor the gods and ancestors—living up to the standard set by the old stories.

Final Thoughts

In Viking culture, giving your word was akin to making a sacred bond, and walking it back—especially without good reason—would be a severe blow to one’s honor. The resulting loss of trust could have real social and even existential consequences in a tightly knit community.

While modern life is far removed from the Norse era, many who embrace or admire Viking values see honesty and reliability as pillars of that tradition. Thus, from this perspective, consistency in word and deed isn’t just a polite social norm; it’s a core component of personal honor and communal respect.

The Ephemeral Flame of the North: A Philosophical Odyssey through the Realm of the Vikings

In the depths of the boreal expanse, where the aurora borealis dances across the sky like a spectral bride, there existed a people whose essence was as elusive as the wind and as unforgiving as the winter’s grasp. The Vikings, those enigmatic sons of Odin, left behind a legacy that is at once a testament to their unyielding spirit and a mystery that beckons us to delve into the labyrinthine corridors of their culture. This essay is an attempt to navigate the philosophical underpinnings of Viking society, to unravel the threads of their worldview, and to illuminate the esoteric dimensions of their existence.

At the heart of Viking philosophy lies the concept of wyrd, a term that defies translation but approximates to fate or destiny. Wyrd is not merely a predetermined course of events but an active, dynamic force that weaves the tapestry of existence. It is the Vikings’ acknowledgment of the intricate web of causality that binds all things, a recognition that every action, every decision, sends ripples through the fabric of reality. This understanding of wyrd as an omnipresent, omniscient force underscores the Viking belief in a universe governed by laws both natural and divine.

The Vikings’ relationship with nature was not one of domination but of symbiosis. They saw themselves as part of the natural world, not apart from it. Their gods and goddesses were not distant, unapproachable deities but beings intimately connected with the land, the sea, and the sky. Thor, the god of thunder, wielded his hammer Mjolnir not just as a weapon but as a tool to maintain the balance of nature, to ensure the cycle of seasons and the fertility of the earth. Freyja, the goddess of love and fertility, was also the goddess of war and death, symbolizing the Vikings’ acceptance of life’s dualities.

Their cosmology, as depicted in the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda, presents a universe born from chaos, where the primordial giant Ymir and the great serpent Jörmungandr embody the eternal struggle between order and disorder. The Vikings’ world was one of contrasts: light and darkness, fire and ice, creation and destruction. This dichotomy is reflected in their concept of honor, which was not merely a personal virtue but a communal one, tied to the reputation of the family and the clan. Honor was the thread that held society together, the glue that bonded warriors in battle and the standard by which one’s worth was measured.

The Vikings were a people of action, their philosophy manifest in their deeds rather than in abstract speculation. Theirs was a world of doing, where one’s character was revealed through actions, not words. The berserker, that frenzied warrior who fought with a fury that seemed almost divine, was the embodiment of the Viking ideal of courage and strength. Yet, this ferocity was balanced by a deep sense of loyalty and hospitality, virtues that were considered essential to the Viking way of life.

Their art and literature, as preserved in the runestones and the sagas, speak of a people deeply concerned with the human condition. The Vikings pondered the mysteries of life and death, of fate and free will, in stories that were both entertainments and teachings. The Völuspá, the first poem of the Poetic Edda, is a prophetic vision of the end of the world, a reminder of the transience of all things and the inevitability of change.

In their funerary rites, the Vikings demonstrated a profound respect for the dead, believing that the soul continued its journey into the afterlife. The ship burials, with their treasures and provisions for the journey, were not merely displays of wealth but expressions of the Vikings’ belief in an afterlife that mirrored this one. Valhalla, the great hall of the slain, where warriors fought by day and feasted by night, was the ultimate destination for those who died in battle, a place where honor and glory were eternal.

The Viking worldview was not static; it evolved over time, influenced by their encounters with other cultures. Their conversion to Christianity marked a significant shift, as they adapted the new faith to their existing beliefs, creating a unique synthesis that preserved much of their pagan heritage. This blending of traditions is a testament to the Vikings’ pragmatic approach to religion, their recognition that truth can be found in many forms.

As we delve into the philosophical dimensions of Viking culture, we are reminded of the impermanence of all things. The Vikings, with their keen awareness of mortality, lived in the present, cherishing each moment as a gift. Theirs was a philosophy of carpe diem, of seizing the day, for in the words of the Viking proverb, “Cattle die, kinsmen die, you yourself will die, but one thing I know that never dies: the judgment of a dead man’s deeds.”

In the end, the Vikings leave us with more questions than answers, their culture a labyrinth of contradictions and paradoxes. They were warriors and poets, pagans and Christians, individualists and communalists. Yet, it is in these contradictions that we find the essence of their philosophy, a worldview that embraced complexity and ambiguity. The Vikings remind us that life is a journey, not a destination, and that our deeds, not our words, are the measure of our character.

As the flame of the Viking Age flickers out, leaving behind only embers of memory, we are left to ponder the wisdom of their way of life. In a world that values certainty and clarity, the Vikings offer us a different path, one that celebrates ambiguity and uncertainty. Their philosophy is a reminder that truth is multifaceted, that reality is complex, and that the human experience is a tapestry woven from countless threads.

In the silence of the boreal night, under the watchful gaze of the aurora borealis, we can still hear the whispers of the Vikings, their voices carried on the wind. They speak to us of a world that was, of a people who lived and loved and laughed and fought. They remind us that we are not alone in this vast and mysterious universe, that we are part of a larger whole, connected to all that has been and all that will be.

And so, we return to the beginning, to the concept of wyrd, that mysterious force that weaves the tapestry of existence. The Vikings understood that our lives are not our own, that we are part of a larger narrative that unfolds with each passing moment. Their philosophy is a call to embrace this uncertainty, to find meaning in the midst of chaos, and to live each day with purpose and passion.

In the end, the Vikings teach us that life is a journey, not a destination. It is a path that winds through the mountains and valleys of existence, a road that is fraught with danger and filled with wonder. And it is on this journey, in the midst of uncertainty and ambiguity, that we find the true meaning of the Viking way of life.

The issues of immigration, racism, and the Vikings and how it relates to Heathenism..

This post is related to an issue explained here, of there being problems with some very bad racist types being attracted to Heathenism. In this post below I explain why racism never was a valid part of Viking culture, and why racist attitudes are not a valid part of Heathenism. The issue of immigration is strongly tied in with the issue of racism. The Vikings were in their day some of the most well traveled people, that settled all over the place in far off lands, thus immigration was strongly tied into Viking culture as a way of life.

I believe that people should be allowed to immigrate to other countries and given opportunities to do so. The culture of a place grows when the people of that country are exposed to the culture of other ethnic groups. All throughout all of human history the greatest leaps in technology and human ideas have come about though the interaction of different ethnic cultures together. Without this culture exchange of ideas between ethnic groups, cultural ideas tend to stagnate and impede social progress. The mixing together of new things from other sources is the way all things in the universe grow stronger. When only the same is being constantly mixed together, things become weakened. This is a law of how nature itself works. In more ancient times in which war between different ethnic groups was very common, this process of the need to gather in ideas and even as well DNA from other ethnic groups happened through the process of war.

When an enemy was defeated their women would be captured and then be made to be part of the conquering group, and of course these women would in time be made to marry the men of the conquering group, and some taken as slaves also (and likely made to provide sexual pleasure for the men who have enslaved them). As well some of the men of the group that has been defeated may be made to be slaves, but the ancient world concept of slavery generally included the chance for the slave to eventually work their way toward being a free person again. Of course freed slaves would then become a normal part of the culture group they had previously been enslaved in, and likely also reproduce within that group and contribute to the diversity of the group’s DNA.

Also in some cultures such as the northern ones which the Vikings derived from, it was common to encourage travelling strangers that visit to sleep with your wife so that new DNA can be interjected into the group, and then the man would adopt any child that resulted as his own (this practice is shown in the Rígsþula from the Poetic Edda). Another practice common with the Vikings, and the cultures the Vikings derived from, was the exchange of hostages when a war does not have a clear winner and it is decided to call a truce. The Norse form of hostage exchange involved the hostages becoming part of the new group they are made to live in and then living by it’s culture and social rules. Of course many such hostages then would end up marrying into people from the group they have now come to life with, and the children of the hostages would become a normal part of this new group. Thus from all these things in no way did the DNA or even the culture of various groups stay the same. It was always mixing with outside ethnic groups and thus keeping the culture and physical health of that ethnic group strong by mixing in elements from the outside.

The concept of different human “races” is a 19th century idea that has no basis in actual science or reality. Even cultural groups such as the Vikings had no concept of different ethnic groups, only the concept of people from other tribes, or people that follow different gods/goddesses than them (but they even did not until the late period have the concept of different religions). This concept of people from other tribes had nothing to do with the physical appearance of the other people, but instead only on that groups social allegiance. In truth the physical makeup of any ethnic group is just a mixture of different physical traits which that group of people evolved towards over long periods of time living in a certain area of the planet. Humans over long periods of time if they live in smaller isolated groups (as was the case in the past) will physically develop traits that help them best able to adopt to the weather and climate conditions of their area. These are well known facts by anyone with any knowledge of the social sciences, but unfortunately there are many people out there who are afraid of loosing their own ingrained ethnic culture and have backwards 19th century ideas of there being different human “races”. This issue is further encouraged by the fact that many US governmental bureaucratic forms that people have to fill out, which incorrectly ask a person what their “race” is. It would be more correct to ask what someone’s ethnic background is. Ethnic background is related to the language a person speaks and the related social culture that language group has developed.

As Heathens it is good to take after the culture and values which the Vikings had. They were explorers that enjoyed travelling long distances to explore other lands. Clearly if they did not enjoy experiencing other cultures they would not have been willing to spend so much time and effort to travel the long distances they did for trade and exploration. It can be stated that it is likely the Vikings were the most curious of all groups about other cultures and wishing to see and experience foreign distant lands with different ways, as that is exactly what they did. Even Buddha statues have been found in Viking treasure hoards, which shows their interest in artifacts from other cultures. Vikings were known to become employed in distant lands as mercenaries. Many Viking tribes ended up settling all over the place and the Viking culture spread and mixed with and enhanced other cultures. The Vikings themselves did immigrate to many lands. Thus to say that others should not be afforded the same rights is rather hypocritical, and even goes against the values of honor which is an important value in Heathen culture. Another side to this is that welcoming those from other lands is an aspect of hospitality. We as Heathens need to extend our own values towards the interactions we have with all people, not just with other Heathens, otherwise this makes what we believe in only a facade to impress others of our own faith, and not something we truly are practising or believe in.