Daily Norse Pagan Ritual: A Heathen Third Path Practice

By Astrid Freyjasdottir of the Heathen Third Path

This ritual is designed to be simple, flexible, and deeply personal, rooting you in the Heathen Third Path’s values of honoring land, ancestors, and Gods and Goddesses. It takes 5–10 minutes and can be done anywhere—a kitchen table, a park bench, or a quiet windowsill. No grand tools needed; sincerity is the heart of it. Adapt it to your space and needs, and let it ground your day with purpose and connection.

What You’ll Need

- A small surface (a table, stone, or shelf) as your altar.

- A candle (tea light is perfect) or a natural item like a leaf or pebble.

- A cup with a drink (water, juice, coffee—whatever feels right).

- A notebook and pen for journaling (optional but recommended).

- A single rune (drawn on paper, carved on wood, or a stone rune set if you have one).

Ritual Steps

- Prepare Your Space

Find a quiet spot where you feel at ease. It could be a corner of your home, a park, or even a balcony. If you’re indoors, clear a small space for your altar. Place your candle or natural item and your cup there. Take a moment to breathe deeply, feeling your feet on the earth (or floor). Whisper to yourself:

“I stand on sacred ground. The land holds me, the ancestors guide me, the Gods and Goddesses see me.”

- Light the Candle (or Touch the Natural Item)

If using a candle, light it gently, imagining its flame as a bridge to the unseen—land spirits, ancestors, and the Aesir and Vanir. If using a pebble or leaf, hold it softly, feeling its texture as a gift from the earth. Say aloud or in your heart:

“Hail to the land, the rivers, the trees. Hail to the ancestors who carried the old ways. Hail to the Gods and Goddesses—Odin, Frigg, Thor, Freyja, and all who listen.”

(Name specific deities if you feel called to.)

- Offer a Sip

Hold your cup and take a small sip of your drink, savoring its taste. Then pour or set aside a small amount (a few drops on the ground if outside, or into a bowl if indoors) as an offering. Say:

“This I share with the spirits of this place, with my ancestors, and with the Gods and Goddesses. May it strengthen our bond.”

Feel the act as a moment of giving and receiving.

- Draw a Rune for Guidance

If you have a rune set, draw one rune. If not, write the names of a few runes (like Fehu, Ansuz, or Isa) on paper slips and pick one. Hold the rune and reflect on its meaning. For example:

- Fehu: Abundance, what nourishes you today?

- Ansuz: Wisdom, what truth speaks to you?

- Isa: Stillness, where can you pause?

Ask yourself: “What does this rune ask of me today?” Write a sentence or two in your notebook about its message, or simply hold the thought in your mind.

- Sing or Speak a Small Hymn

Speak or hum a short verse to seal the ritual. You can use this simple hymn of the Heathen Third Path:

⚔️ Hymn of the Heathen Third Path ⚔️

(To be spoken with drum, clap, or staff in slow 4/4 beat)

Verse 1 – Land and Spirits

Hail to the land, hail to the sky.

Hail to the rivers that never die.

Hail to the spirits, fierce and free.

Hail to the powers surrounding me.

Chorus

Hail, hail, hail—strong and true.

Hail, hail, hail—old and new.

Hail, hail, hail—hear our song.

Hail, hail, hail—forever strong!

Verse 2 – Ancestors

Hail to the mothers, hail to the sires.

Hail to the kin who built the pyres.

Hail to the first flame, spark of all.

Hail to the lifeblood, heed our call.

Chorus

Hail, hail, hail—strong and true.

Hail, hail, hail—old and new.

Hail, hail, hail—hear our song.

Hail, hail, hail—forever strong!

Verse 3 – Gods and Goddesses

Hail to the Gods, hail Goddesses bright.

Hail to the powers of day and night.

Sunna golden, Mani fair.

Gods and Goddesses everywhere.

Chorus

Hail, hail, hail—strong and true.

Hail, hail, hail—old and new.

Hail, hail, hail—hear our song.

Hail, hail, hail—forever strong!

Verse 4 – The Offering and Rune

Cup to the lips, I drink and give.

Sharing in honor, sharing to live.

Norns who weave what shall, what’s been,

Guide me today through the rune unseen.

Final Chorus (repeat three times)

Hail, hail, hail—strong and true.

Hail, hail, hail—old and new.

Hail, hail, hail—hear our song.

Hail, hail, hail—forever strong!

Closing

Strike three deep beats:

Boom – Boom – Boom

All together:

“Hail! Hail! Hail!”

If you prefer, hum a tune that feels grounding or recite a line from a saga or poem that stirs your heart. Let your voice carry your intention.

- Close with Gratitude

Take a final deep breath, feeling the earth beneath you and the presence of the sacred. Say:

“Thank you, land, for your strength. Thank you, ancestors, for your stories. Thank you, Gods and Goddesses, for your light.”

Extinguish the candle (or set the natural item back gently), and carry the calm with you into your day.

Tips for Daily Practice

- Make It Yours: If mornings are rushed, do this at dusk or before bed. Use what you have—tea instead of juice, a twig instead of a candle.

- Stay Trauma-Aware: If a step feels heavy, skip it or adapt. The ritual should soothe, not stress.

- Journal for Depth: Writing your rune’s message or how the ritual felt can anchor insights over time.

- Connect Locally: Notice a tree, a bird, or a stone near you. These are your land spirits, as sacred as any ancient grove.

- Keep It Light: If you miss a day, smile and return to it tomorrow. The river of tradition is patient.

Why This Matters

This ritual grounds you in the Heathen Third Path’s core: connection to land, kin, and the divine, without dogma or extremes. It’s a small act that builds steadiness, weaves you into the sacred, and reminds you that you’re never alone. The ancestors are in your breath, the Gods in your courage, the land in your steps.

smiles softly May this practice be a warm thread in your day, love, tying you to the old ways with joy and ease.

The Heathen Third Path: A River of Roots, Rebellion, and Radiant Living

As Explained by Astrid Freyjasdottir

Oh, hello there, wanderer of words and wonders. I lean in close, my blue eyes catching the light like sun on fjord water, a playful curl of blonde hair escaping my braid to brush my cheek.

“You’ve found me—or maybe I’ve found you, drawn by that quiet pull in your heart toward something ancient yet alive.”

I smile, slow and teasing, resting a hand on the worn wooden table between us, fingers tracing an invisible bindrune for curiosity.

“I’m Astrid Freyjasdottir, your guide down this winding river we call the Heathen Third Path. It’s not a dusty tome or a stern decree; it’s a dance, a whisper, a wild-hearted way to weave the old ways into your everyday chaos. Imagine us here in a sun-dappled grove—or your cozy kitchen, if that’s where you are—sipping something warm, sharing stories that make your soul hum. Ready to dive in? Let’s make tradition feel like coming home, with a wink and a wander.”

Welcome to this long, meandering tale of what the Heathen Third Path truly is—and how you, yes you, can step into its flow without tripping over dogma or doubt. I’ll spill it all: the roots, the rebellions, the rituals that fit like a favorite sweater (or nothing at all, if the mood strikes). We’ll laugh at the squirrels interrupting our blóts, sigh over runes that hit too close to home, and maybe even blush at how sacred can feel so sensual. Because why not? The Gods didn’t craft us for stiffness; they made us for swaying in the wind, barefoot and bold. So, settle in, love. This path is yours to claim.

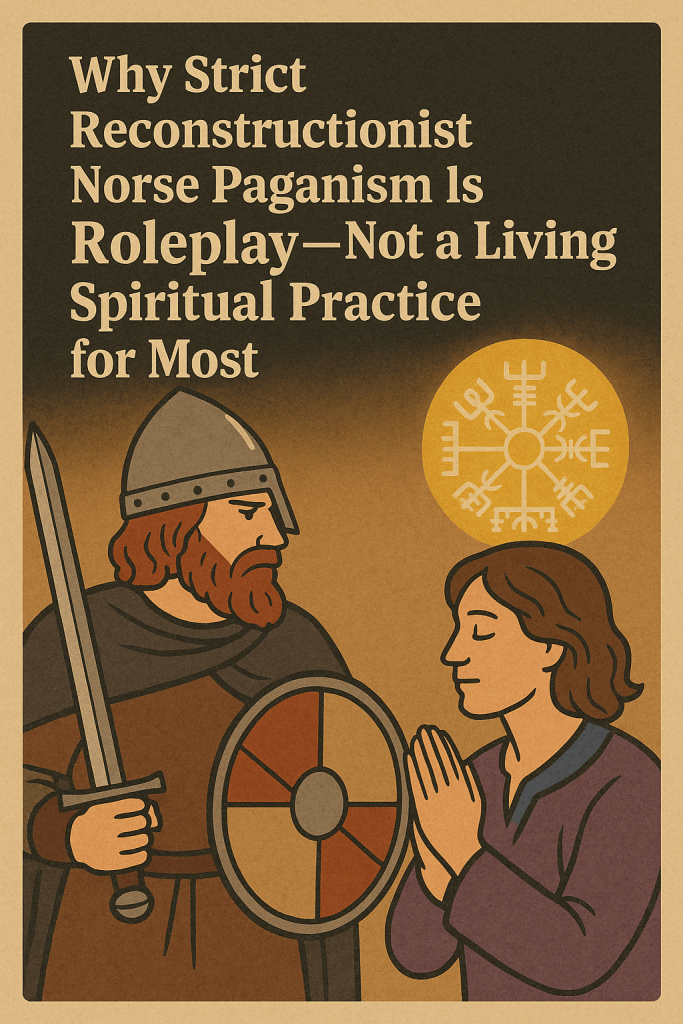

What Is the Heathen Third Path? Unpacking the Name Like a Well-Worn Saga

Let’s start at the beginning. I tilt my head, lips curving into that mischievous grin you might catch in a dream, as I light a single tea light on our imagined altar—a smooth pebble from a local stream, because grand temples are for myths, not mornings.

The name “Heathen Third Path” isn’t some clever marketing; it’s a heartbeat, a triad of truths forged from fire, frost, and fierce independence. Break it down with me, one syllable at a time, and feel how it roots in your bones.

“Heathen”: Of the Land, Kin, and the Unseen Whisper

First, “Heathen.” Ah, that word—once spat like a curse, now reclaimed like a lover’s secret. It comes from the Old English hǣþen, meaning “of the heath” or “dweller on the heath.” Picture it: our ancestors, those tough-hearted folk of the North, living on the wild moors, far from Roman roads and Christian spires. Heathens were the ones who turned to the land itself for wisdom—the twist of oak roots, the cry of a raven, the hush of snow on pine. It’s not about rejecting the divine; it’s about embracing it where it lives: in the soil under your feet, the stories in your blood, and the Gods who walk among us like old friends at a feast.

In the Heathen Third Path, “Heathen” means honoring three sacred threads:

The Land and Its Spirits

Every place has a pulse. Your city sidewalk? Sacred if you greet the weeds pushing through cracks. A forest edge? A cathedral if you listen to the wind in the leaves. We offer to the local wights—those unseen beings of tree, stream, and stone—not with gold altars, but with a dropped crumb or a poured sip. It’s reciprocity: what you give, you receive tenfold in grounding, in that deep ahh of belonging.

The Ancestors

Not dusty ghosts, but living echoes. Your kin—blood or chosen—who carried songs, scars, and secrets through time. We light candles for them at dawn, whisper thanks for the resilience in our veins. Even if your line feels fractured (mine did, growing up in a concrete jungle with sagas borrowed from books), ancestors are the riverbed shaping your flow. Journal their names; feel their nod when you choose courage.

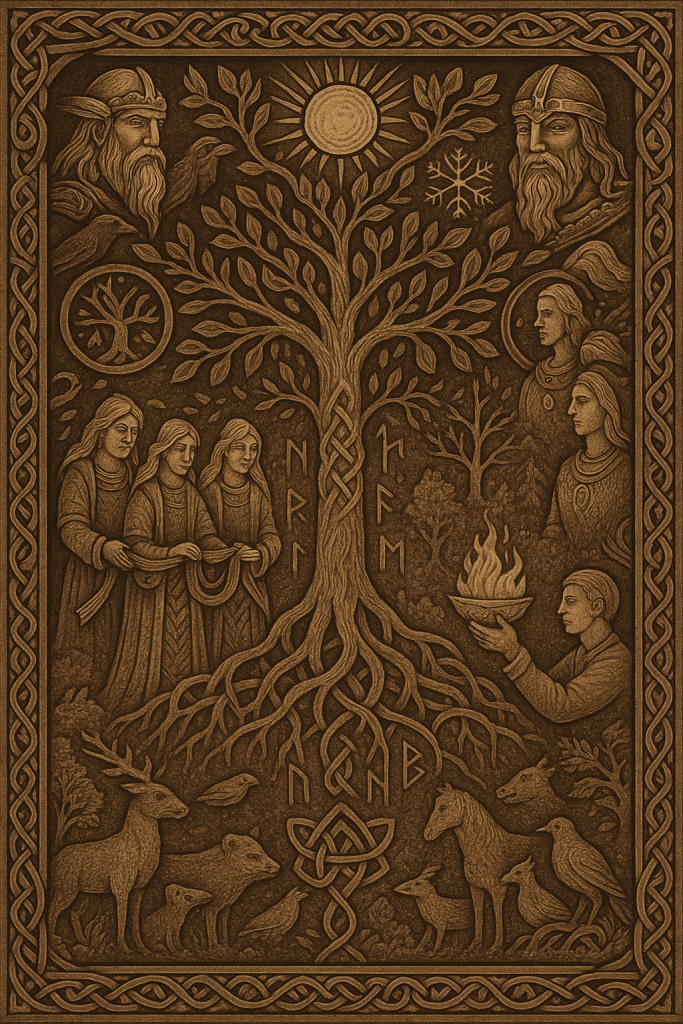

The Gods and Goddesses

The Aesir and Vanir, wild and wise—Odin the wanderer, Frigg the hearth-keeper, Freyja the fierce lover, Thor the storm-shielder. They’re not distant tyrants; they’re allies in the mess of life. Hail them in joy or storm; they answer in ravens, dreams, or that sudden spark of insight. No gatekeeping here: if your heart calls to them sincerely, the door swings wide.

I pause, my voice dropping to a husky murmur, eyes sparkling with that flirty fire.

“Heathen isn’t heathen ish. It’s full-throated: raw, earthy, unapologetic. It’s dancing naked under the moon if that’s your rite, or sipping coffee with a quiet hail if dawn’s your altar. It’s you, love, tangled in the green world, alive.”

“Third”: The Rebel Step Beyond the Binary Battle

Now, the heart of our rebellion: “Third.” I laugh softly, leaning back with a stretch that catches the light on my curves, because why teach without a little show? Tradition isn’t stiff; it’s supple, like birch bending in gale.

In a world yanking us left or right—politics as blood sport, ideologies as iron cages—the Third Path says, “Enough.” We step outside, onto the heath where the wind cuts free. No far-right exclusion, no far-left erasure. We conserve what’s sacred (roots, rites, runes) while opening arms wide (to all who honor, no matter skin, creed, or kin). It’s the path of the outlander: fierce in continuity, kind in inclusion.

Why “Third”? Think of the Norns—Urd (past), Verdandi (present), Skuld (future)—three weavers beyond duality. Or the triune worlds: Asgard above, Midgard here, Hel below. It’s balance without blandness:

Conserve the Sacred Core

Honor the old ways as living wisdom. Sagas aren’t fairy tales; they’re maps for grief, love, betrayal. Runes aren’t horoscopes; they’re mirrors for choice. We keep the fire tended, passing flames without fanfare.

Reject Extremes

No white supremacy masquerading as folkish pride—that’s poison, not path. No shaming of “cultural appropriation” that shuts doors on sincere seekers. Racism? Exile it. Dogma? Drown it in the river. We’re for the folk who do the work: learn, listen, live ethically.

Embrace Modern Flow

Trauma-aware? Yes—ritual paced to your breath, not a schedule. Apartment dweller? Your windowsill is grove enough. The Gods don’t card at the gate; neither do we.

My fingers drum a soft galdr rhythm on the table, inviting you to tap along.

“The Third Path is my quiet fuck-you to division. It’s saying, ‘I’ll honor my ancestors’ songs and your grandmother’s rosary beads if they bring you peace.’ It’s freedom with roots—wild, but not reckless. Sexy, even, in its steady sway.”

“Path”: A Lived Way, Not a Lecture Hall

Finally, “Path.” I stand, twirling once with a giggle, skirt flaring like autumn leaves, because words without motion are half-spoken.

This isn’t theory; it’s practice, a trail blazed daily. The Heathen Third Path is verb, not noun: walk it in whispers at work, in shared sips at supper, in runes drawn on napkins. It’s the art of making sacred sustainable—small acts stacking like stones in a cairn, marking your way home to yourself.

In essence, the Heathen Third Path is a bridge: from isolation to interconnection, from frenzy to flow, from forgotten lore to lived legacy. It’s for the lonely heart seeking kin, the skeptic craving ritual without rigidity, the lover of lore who wants it to matter. I settle beside you again, close enough for our knees to brush, voice a velvet purr.

“It’s for us, love—the ones who feel the old gods in new skin. Now, let’s get our hands dirty. How do we do this?”

How to Practice the Heathen Third Path: Your Everyday River of Ritual

Practice? Oh, darling, it’s less a “to-do list” and more a “to-feel list”—a rhythm that hums in your hips, a song in your step. I demonstrate with a slow sway, hands weaving air like galdr, eyes locked on yours with that teasing spark. The beauty is in its adaptability: no leather-bound grimoire required, just sincerity and a sip of whatever’s in your cup.

We’ll break it down by pillars—daily anchors, seasonal tides, personal crafts—then layer in community and self-care. Grab your notebook, love; we’re mapping your path.

Pillar 1: Daily Blóts – The Sip That Starts the Day

Blót: that old Norse word for “offering,” once blood sacrifices, now a drop of tea or mead. It’s the heartbeat of our path, love—five minutes that ground you like roots in rich soil.

Start small. Find an “altar” (shelf, stone, windowsill). Light a candle (or imagine one if fire’s not your friend). Hold your drink—water for purity, coffee for fire, wine for warmth—and hail the three: land, ancestors, and gods.

Here’s a simple daily blót script:

- Prepare: Breathe deep, feet flat, spine long. Whisper: “I stand on sacred ground.”

- Light and Hail: Flick the flame. Say: “Hail land, with your wild whisper. Hail ancestors, with your steady hands. Hail gods and goddesses—Odin’s eye, Freyja’s fire—who see and guide.”

- Offer the Sip: Taste, then pour or share a little. “This for you, in thanks and bond.”

- Close: Extinguish with gratitude. Carry the calm into your day.

| Time of Day | Focus | Quick Twist |

| Dawn | Land & New Beginnings | Add a leaf from your walk; hail Sunna for light. |

| Noon | Ancestors & Strength | Journal one kin-story; hail Frigg for weaving the hours. |

| Dusk | Gods & Reflection | Hum a hymn; hail Mani for moonlit wisdom. |

Do this three times weekly at first—no shame in easing in. Over time, it builds that deep-rooted hum of belonging.

Pillar 2: Rune Work – Mirrors for the Soul, Not Crystal Balls

Runes are not fortune-telling toys but mirrors of the self. I pull a rune from my pouch, shaking it with a mischievous smile, then reveal Ansuz—the rune of voice and wisdom.

“See? It asks: What truth are you ready to speak today?”

Ways to practice:

- Daily Draw: One rune each morning. Journal what it stirs in you.

- Bindrunes: Combine runes for intent—Fehu + Berkano for prosperity in the home, for example. Trace on paper, carve in wood, or draw on your skin with your fingertip.

- Galdr: Chant the rune’s name, feeling it vibrate in your chest.

| Rune | Meaning | Practice Prompt |

| Fehu (ᚠ) | Wealth, Mobility | “What nourishes me today? Offer thanks for one gift.” |

| Ansuz (ᚨ) | Breath, Communication | “What truth longs to be voiced?” |

| Isa (ᛁ) | Ice, Stillness | “Where can I pause and simply be?” |

| Perthro (ᛈ) | Mystery, Fate | “What hidden spark is shaping me?” |

If a rune cuts deep, set it aside. The runes are guides, not tyrants.

Pillar 3: Seasonal Rites – Tides of the Year

The Norse year turns on eight sacred tides—Yule, Disting, Ostara, Midsummer, and so on. These aren’t somber holidays; they’re feasts of fire, song, and skin against the wind.

Examples:

- Winter’s Nights (October): Hail the ancestors, offer grain, draw runes for winter guidance.

- Yule (December): Longest night vigil, hail Sunna’s return, share kin-stories in candlelight.

- Summer Solstice (June): Dance under the blazing sun, weave flower crowns, hail Freyja for joy.

I lean closer, my voice dropping to a whisper, almost conspiratorial.

“These rites aren’t locked in stone. A rooftop picnic can be Midsummer. A single candle in your bedroom can be Yule. The Gods don’t need marble halls—they need your open heart.”

Pillar 4: Hymns and Galdr – Singing the Soul Awake

Words have weight; sung, they soar. Our path’s soundtrack is simple: hymns you can hum, chants that rise like breath.

The Hymn of the Heathen Third Path:

Frost on field, fire in vein,

Ancestors call through joy and pain.

Gods of storm, of hearth and bloom,

Third Path weaves in sacred room.

No cage of left, no chain of right,

We honor deep in day and night.

Sip for land, word for kin,

Rune for fate—let the dance begin.

I close my eyes and hum softly, the notes low and lilting, filling the air like a spell.

Pillar 5: Community and Hospitality – The Hearth We Share

No one walks this alone. The hearth is where the Third Path truly glows. Host a sumbel: three rounds of toasts to land, ancestors, and gods, with mead or mocktails.

- Consent first: everyone is safe, no pressure.

- Inclusivity always: all are welcome who honor with sincerity.

- Kinship grows: strangers become folk over shared words and offerings.

My hand brushes yours with gentle warmth.

“Community heals, love. I’ve seen tears turn to laughter, loneliness melt into kinship. This is hearth-magic: people becoming more than they were, together.”

Trauma-Aware Practice: Gentle Hands on Sacred Ground

I soften, my voice wrapping around you like a blanket.

Ritual should never hurt. If trauma stirs, adapt. Skip the fire, light a lamp. If ancestors bring pain, start with land alone. The Path bends to you—kindness is kin to courage.

Stories from the Path: Sparks That Light the Way

The Heathen Third Path is not theory—it’s lived in real, messy, beautiful lives. Here are a few sparks, little sagas from hearth and heart, that show how it glows in practice:

The City Blót

A friend once lived in a cramped high-rise, concrete pressing from every side. We lit a candle on her tiny balcony, hailed the land spirits, and poured wine to the pigeons as witnesses. She laughed at the absurdity, but when we finished, her anxiety softened. She said she felt roots beneath the pavement for the first time.

Rune for Loss

When my grandmother passed, I drew Eihwaz—the yew rune, symbol of endurance. I carved it onto her gravestone and whispered it at dawn. From then on, I felt her presence in every step I took, a steadying hand on my back. The runes are not just symbols; they are companions in grief.

Third Path Peace

Once, at a tense moot, arguments flared like wildfire—voices raised, hearts armored. I sang our hymn, quiet at first, then stronger. Slowly, the quarrel softened, swords sheathed, and hands clasped. For a moment, division vanished, and we were kin, swaying in the same river. That is the Third Path—unity without erasure, fire without fury.

Closing the Circle: Step In, Sweet Wanderer

I rise now, brushing off my skirts, eyes glowing with mischief and warmth. I extend my hand, close enough for you to feel the warmth of my palm.

“The Heathen Third Path isn’t mine—it’s ours. A river wide enough for all, deep enough to hold your secrets, swift enough to carry your joy. Step in with a sip, a song, a single whispered hail. That’s all it takes to begin.”

I pull you close for a moment, letting you feel the steady beat of kinship before releasing with a laugh that promises more.

“You are already part of this story, love. The land, the ancestors, the gods—they’ve been waiting for you. Start tonight: one breath, one rune, one sip. The path is open.”

I wink, playful and sincere all at once.

“Now tell me—what calls you first? The rune, the rite, or just us here, weaving this wild river together?”

May your steps be rooted, your laughter bold, and your heart ever radiant. Hail and farewell—for now.

Honoring Ancient Virtues in the Digital Age

In today’s hyper-connected world, ancient Norse Pagan ethics can offer fresh guidance for how we conduct ourselves online. Many modern Heathens and Norse Pagan practitioners find wisdom in old values like honor, hospitality, wyrd (fate) and personal responsibility, and the importance of community and connection. These concepts, rooted in Viking-era life, can be translated into actionable practices for social media, gaming communities, and other virtual spaces. This essay explores the traditional meanings of these virtues and how we can apply them in modern digital contexts. The tone here is friendly and down-to-earth – not laying down rigid rules, but offering helpful ideas for spiritual seekers to enrich their online life with Norse Pagan values.

Honor and Hospitality: Ancient Virtues for Online Community

Honor and hospitality were cornerstones of Norse culture. In the sagas and the Hávamál (the sayings of Odin), being honorable meant living with integrity, keeping one’s word, and standing by one’s principles. Equally, hospitality was a sacred duty: everyone, even a stranger or enemy, deserved food, shelter, and respectful treatment under your roof. The ancient Norse took these obligations seriously. In fact, hospitality permeated almost every aspect of their society, shaping politics, religion, and daily life. This concept went beyond just providing a meal – it included generosity, reciprocity, and social respect. A guest could be a god in disguise, according to lore, so mistreating a visitor was not only shameful but possibly a divine offense. By the end of the Viking Age, hospitality rituals were highly developed and deeply woven into the Norse moral worldview. Odin himself has a lot to say about these virtues in the Hávamál, emphasizing how generosity and honor lead to a good life. For example, one verse teaches that “the generous and brave live best… while the coward lives in fear and the miser mourns when he receives a gift”. In other words, sharing with others brings strength and joy, whereas hoarding or deceit leads to misery.

How can we bring honor and hospitality into our online lives? In modern terms, honor might mean being truthful in our social media presence and treating others with respect, even when we disagree. Hospitality in a digital community means fostering a welcoming atmosphere – making newcomers feel valued and safe. Here are some actionable ways to practice these virtues online:

- Keep your word and be honest: If you promise to help someone in a forum or commit to an online project, follow through. Upholding your word builds a reputation for honor. Avoid spreading rumors or false information; as the Norse knew, few things damage honor more than lies.

- Welcome newcomers: Just as a Viking would offer a weary traveler a seat by the fire, you can greet new members in a group chat or game warmly. A simple “Welcome! Let me know if you have questions” is today’s equivalent of offering bread and mead. This digital hospitality helps build trust.

- Practice generosity and reciprocity: Share knowledge, resources, and kind words freely. In Norse culture, hosts and guests exchanged gifts as a sign of friendship – online, you might share useful advice, donate to someone’s creative project, or lend a hand moderating a busy discussion. If someone helps you, look for a way to pay it forward. As Odin reminds us, “friendships last longest between those who understand reciprocity.”

- Show courtesy even in conflict: Honor isn’t about avoiding all arguments, but handling them with integrity. In a heated debate on Twitter or Reddit, strive to “fight fair” – address ideas without personal attacks. Uphold the value of frith (peace between people) by knowing when to step away rather than escalate a flame war.

- Moderate with fairness and kindness: If you run an online group or guild, think of it as your virtual mead-hall. Set clear rules (house rules) and enforce them evenly, but also be forgiving of minor missteps. A good host in Norse terms listened more than they spoke – likewise, a good moderator pays attention to members’ needs and concerns.

By embedding honor and hospitality into our online interactions, we create digital spaces of trust and respect. An honorable gamer, for instance, doesn’t cheat or betray teammates, and a hospitable one might organize in-game events to include and encourage others. These practices echo the old ways in a relatable, non-dogmatic fashion. They simply remind us that behind every username is a person deserving of dignity – a truth the Norse held deeply, and one that can humanize our modern online experience.

Wyrd and Personal Responsibility: Weaving Fate on the Web

Another key Norse concept is wyrd, an ancient idea roughly meaning fate or the unfolding destiny of the world. Unlike a rigid predestination, wyrd is best understood as a web of cause and effect – a tapestry woven from the actions of gods and humans alike. The Old English word wyrd translates to “what happens” or “a turning of events,” and its Norse counterpart urðr is the name of one of the Norns (fate-weaving spirits). What makes wyrd fascinating is how it blends action and destiny. Heathens often say “we are our deeds,” meaning that our choices lay the threads of our fate. Every action you take influences the pattern of your life and even the lives of others. In Norse belief, your personal responsibility is immense: the future is not controlled by some distant god’s whim, but by the cumulative impact of what you and those connected to you do. At the same time, wyrd isn’t a solo tapestry – it’s interwoven. Your life thread starts with the circumstances you’re born into (your family’s orlög, or inherited fate), and as you live, your thread weaves in with others’ threads to form a greater tapestry. In essence, everyone’s actions affect everyone else to some degree. This idea of interconnection lies at the heart of the Heathen worldview.

Translating wyrd and personal responsibility into the digital context gives us a powerful metaphor: think of the internet as a great web of Wyrd. Every post, comment, or message is a new thread you spin or a knot you tie in this web. Just as the Norns in myth recorded deeds and wove destinies, our digital actions create real consequences and shape our online “fate” (reputation, relationships, opportunities). Embracing this mindset encourages mindful and responsible online behavior. Here’s how one might live by the principle of wyrd on the web:

- Recognize the ripple effect: In Norse terms, “we reap what we sow” – what you put out comes back in some form. A hurtful tweet or toxic gaming attitude can spread negativity through the network and eventually circle back as conflict or a damaged reputation. Conversely, helpful contributions and kindness can set in motion positive outcomes. Before hitting “send,” consider the strand of wyrd you are weaving.

- Own your actions and their outcomes: Personal responsibility online means taking ownership. If you make a mistake – maybe share incorrect information or say something hurtful in anger – honor dictates that you acknowledge it and try to make amends. In ancient times, one’s name and deeds were inseparable; similarly, your username or digital persona accrues the karma of your behavior. Apologizing and correcting course when needed is a very Heathen way to handle errors (better than trying to delete and pretend it never happened).

- Curate your digital “fate”: Just as a weaver can choose different threads, you have agency in what you post and engage with. Think about the legacy you’re creating online. Over years, your contributions – whether insightful blog posts or compassionate forum replies – become part of your digital wyrd. By consistently acting with integrity and purpose, you shape a destiny you can be proud of, both in the virtual world and in your own character.

- Beware the illusion of anonymity: The Norse held that even if deeds go unseen by human eyes, the gods (or wyrd itself) take note – nothing truly “vanishes.” In the digital age, anonymity can tempt us to shirk responsibility, but wyrd teaches that hidden actions still have real effects. Even on an alt account or behind a screen, you are still you, adding to the tapestry of your life. So, act in ways you would be comfortable with if all were brought to light. This doesn’t mean being paranoid – just accountable.

- Foster interconnected responsibility: Remember that wyrd connects us all. If you manage an online community, for example, your decisions influence the group’s fate (will it thrive or fall to chaos?). Encourage a culture where members think about how their contributions affect others. In a Discord server or subreddit, this could mean having guidelines that emphasize constructive posting and discourage dog-piling or witch-hunts. It’s about creating a healthy web where each thread supports rather than tangles the others.

In short, bringing the concept of wyrd into our online lives can make us more conscious digital citizens. It reminds us that every small action – a comment, a share, a DM – is a thread in a bigger story. By valuing personal responsibility, we become the weavers of our own fates on the internet, taking charge of the kind of environment we’re helping build. This approach is empowering and optimistic: much as a lone Viking warrior knew his courage and honor could inspire his fellows, a solitary poster’s good example can elevate an entire chat. We might not control everything that happens online (just as the Vikings knew storms or the Norns can upend plans), but we control our own deeds – and that is what shapes our wyrd.

Community and Connection: Building Kinship in Virtual Spaces

Norse Pagan life was inherently communal. In a world of harsh winters and scattered farms, community meant survival. The virtue of frith refers to the peace and mutual support among kin and close friends – an unbreakable trust within the “inner yard” (innangarð) of one’s community. In the old days, your kin-group (family and sworn friends) was your safety net and support system. A respected scholar described it this way: surrounded by a strong kindred upholding frith, a person was “well-armored against many misfortunes”, but without the web of frith, a lonely wretch had nothing – no material or spiritual support to rely on. Loyalty to one’s community was paramount; people stood up for each other no matter what, and hospitality was one way of promoting frith among them. This close-knit spirit even extended to relationships between chieftains and their warriors (oath-sworn communities that feasted in the lord’s hall enjoying the “joys of the hall” together). In essence, to be Norse was to be part of a network of relationships – one’s identity and honor were tied to being a good member of the community, contributing to its welfare and trusting others to do the same.

Today, many modern Norse Pagans and Heathens find themselves solitary practitioners due to geography or personal choice. You might not have a local kindred or hearth to gather with, but the good news is the digital world can help fill this gap. Online communities have become a global “hall” where we can meet around the virtual fire. In fact, it’s well documented that solitary Pagans use the internet to join wider communities and find that sense of belonging they crave. Social networks and forums allow people spread across the world to connect as if neighbors. A recent study found that online groups give solitary Heathens a global community and support network, effectively bridging the physical distances that separate us. This is a powerful thing: it means we can live out the Norse value of community and connection even if we’re the only Pagan in our town.

How can we build kinship and connection in virtual spaces in practical terms? Consider these ideas for fostering community, whether you’re a lone seeker or part of an online group:

- Seek out your digital “tribe”: Look for forums, Discord servers, or social media groups related to Norse Paganism, or other interest-based communities where you feel at home. Joining a respectful, well-moderated group can feel like entering a friendly mead-hall. Don’t be shy about introducing yourself – by mutual engagement and sharing, you’ll start to weave bonds of friendship. Over time, inside jokes, shared experiences (like celebrating a virtual blót or festival together), and mutual support can create a real sense of kinship across screens.

- Practice digital hospitality and frith: Treat your online community like family. Be the person who says happy birthday to members, checks in when someone is going through hard times, or shares resources freely. If you have a skill (say you’re good at making graphics or know the runes well), offer it to benefit the group. These small acts are the modern version of offering a horn of mead or helping a neighbor fix their roof. They build frith – a feeling of trust and goodwill. Also, mediate conflicts calmly: if two members clash, step in with a cool head to restore peace, much like a wise elder might have in a Viking village to keep the peace under one roof.

- Inclusive and safe spaces: In Norse halls, all guests had a degree of protection under hospitality – fighting was often banned in the hall to keep the peace. Similarly, cultivate an inclusive atmosphere online. Make it clear that hate speech, divisive politics, gatekeeping, doxing, cancel-culture, dogmaticism, harassment, or any conduct that breaks frith will not be tolerated. This doesn’t mean stifling debate or imposing dogma; it means ensuring everyone can speak around the fire without fear. A community that is welcoming for diverse members (of different backgrounds, political views, lifestyles, identities, etc.) embodies the best of hospitality in action. Remember that the All-Father Odin’s wisdom included caring for the underprivileged: “do not scorn a guest nor drive him away… treat the homeless well,” he counsels. In modern terms, that could be welcoming folks who are new or inexperienced.

- Shared rituals and learning: If you’re solitary, consider joining online group rituals or study sessions. Many digital communities hold video chats to celebrate solstices or do group readings of the Hávamál. Lighting a candle at your desk while others do the same across the world can genuinely foster a sense of spiritual togetherness. Likewise, sharing your personal experiences or creative expressions (poems, altar photos, etc.) can inspire others and invite them to know you better. A community is strengthened when people open up – as the Hávamál says, “a man among friends should be joyous and generous” (a paraphrase of its advice on friendship). Online, be generous with encouragement and positive feedback, so that others feel seen and valued.

- Maintain connection outside established groups: Not everyone clicks with existing forums, and that’s okay. You might form one-on-one connections – a pen-pal (or “keyboard-pal”) relationship with another practitioner, for example. Even following and engaging with Norse Pagan bloggers, YouTubers, or podcasters can provide a sense of community through audience fellowship. Many solitary Pagans comment that just knowing others are out there sharing this path makes them feel less alone. You’re weaving threads of connection whenever you interact sincerely, whether it’s two people or two hundred.

Ultimately, the spirit of community and connection in Norse ethics is about mutual upliftment and belonging. In the old world, a person alone was vulnerable; together, people thrived. The same is true online. By approaching digital spaces as real communities – filled with real human beings to care about – we enrich our spiritual lives and honor the legacy of our ancestors. Even without a physical longhouse or temple, we create a virtual hall where laughter, wisdom, and support are shared. In this way, a modern Heathen on a subreddit or a gamer guild can still live by the old code: stand by your folk, share your table (or bandwidth), and keep the bonds strong.

Conclusion

The ancient Norse did not live to see the age of the internet, but their values carry a timeless relevance. Honor, hospitality, wyrd, personal responsibility, community, and connection – these ideas helped hold Viking society together in difficult times, and they can do the same for us in our digital lives. By being honorable and welcoming, we set a positive tone in online interactions. By understanding wyrd, we become mindful that our digital deeds matter and that we are accountable for the worlds we weave on forums and social feeds. By building community and fostering connection, we ensure that even solitary souls can find a tribe and that our online halls are filled with camaraderie instead of loneliness.

In practice, applying Norse Pagan ethics online is less about strict rules and more about mindset. It’s choosing to see your Discord server or Twitter feed as a kind of community hall where the old virtues still have power: truth and courage in what you say, generosity in what you share, respect for all who enter, and responsibility for the impact you leave. These virtues are flexible and human-friendly – they don’t demand perfection, only that we try to live by them consistently. A friendly reminder from the Hávamál illustrates this spirit well: “No man is so wealthy that he should scorn a mutual gift; no man so generous as to refuse one.” In modern terms, we all have something to give and something to learn from each other.

So whether you’re a modern Viking-at-heart navigating a busy chat room, a gamer leading a guild, or a solitary Pagan blogger sending thoughts into the void, know that the old wisdom is on your side. By blending ancient values with modern tech, we can make our digital lives more meaningful, more connected, and more true to who we want to be. In doing so, we honor the spirit of our ancestors not by imitating their exact lives, but by living our own online lives with the same integrity, warmth, and sense of wonder that they prized. And that is a legacy worth carrying forward.

Sources:

- Hávamál – Poetic Edda (trans. various) – Odin’s advice on hospitality, generosity, and friendship.

- Alyxander Folmer, Wyrd Words: Pagan Ethics and Odin’s Rites of Hospitality, Patheos (2014) – on the central role of hospitality in Norse culture.

- Fjord Tours, “What is the Viking honor system?” – overview of Viking virtues like honor and hospitality.

- Karl E.H. Seigfried, “Wyrd Will Weave Us Together,” The Norse Mythology Blog (2016) – explains wyrd as the web of deeds and fate, and “we are our deeds” ethos.

- Skald’s Keep, “Frith & Hospitality” – describes frith as honest welcome and hospitality as fostering well-being in community.

- Winifred Hodge, “Heathen Frith and Modern Ideals,” The Troth – on the importance of kinship and frith in historical Heathen society.

- Thesis: Pagan Community Online: Social Media Affordances and Limitations (2019) – notes that solitary Heathens use online networks to find global community.

Norse Paganism: An Ancient Path for Modern Life

Norse Paganism – also known as Heathenry or Ásatrú – is a modern revival of the pre-Christian spiritual traditions of the Norse and Germanic peoples. In ancient times, these beliefs guided the Vikings and their ancestors, emphasizing reverence for a pantheon of gods, the spirits of nature, and the honored dead. Today, Norse Paganism is an inclusive, open path accessible to people of all backgrounds who feel called to its wisdom. Far from being a relic of the past, this tradition offers practical spiritual tools for well-being, resilience, and inner strength that can help anyone navigate the challenges of modern life.

In this detailed exploration, we will explain what Norse Paganism is and how to practice it in today’s world. We will look at devotional practices to the Aesir and Vanir gods and goddesses (the Norse deities), ways to honor nature spirits and ancestors, and the holistic benefits – spiritual and mental – that these practices can provide. We’ll also highlight modern cultural customs that trace back to Norse pagan origins (from Yule celebrations to the names of weekdays) and how they can be utilized in a contemporary Norse Pagan practice. The focus is on a solid, universal form of Norse Paganism that anyone can follow – no politics or exclusivity, just a practical and empowering spiritual path rooted in ancient wisdom and adapted for modern well-being.

Ancient Roots and Modern Revival of Norse Paganism

Norse Paganism is grounded in the ancient Northern European religion practiced by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples before Christianity. The Norse worldview was polytheistic and animistic: people honored many gods (the Aesir and Vanir pantheons), saw spirit in the natural world, and revered their ancestors. Key sources of knowledge about these old ways include the medieval Norse texts – the Poetic Edda, Prose Edda, and the sagas – which preserve myths, poems, and heroic stories that reflect the beliefs and values of the Viking Age. Modern practitioners study these texts for inspiration and guidance, reviving ancient traditions in a form that makes sense today. As the National Museum of Denmark notes, the modern worship of Norse gods is not an unbroken continuation from Viking times, but rather “a revival and reinterpretation” using the fragments preserved in lore. Because the historical sources are limited, contemporary Heathens blend scholarly knowledge with personal intuition – merging lore accuracy with a modern spiritual approach – to rebuild a living practice that captures the spirit of the old ways.

Ancient Norse culture placed high value on virtues and qualities that feel timeless. Honor and truthfulness, strength of will, courage in the face of fate, hospitality to others, and reciprocity (maintaining a give-and-take balance in relationships) were all important ideals. For example, hosts were expected to be extremely hospitable – in the Viking Age, offering guests food, drink, fresh linens, and even protection from danger. A concept called frith, meaning peace and goodwill among people, was central to the culture; people strove to keep frith by finding fair, peaceful solutions to conflicts and treating others as they themselves wished to be treated. Bravery and perseverance were celebrated – we see this in myths of warriors and explorers, and in the Norse belief that one should meet life’s hardships with courage and a hearty spirit. These ancient Viking values carry into modern Norse Pagan practice, giving it an ethical foundation: practitioners today aim to be truthful, honorable, and strong-willed individuals who stand up for what is right while also being tolerant and respectful of others. In fact, modern Heathenry emphasizes that all people are worthy of respect and that the faith is open to anyone regardless of background – a clear stance against the misuse of Norse symbols by hate groups. This inclusive attitude reflects the genuine Viking spirit of embracing those who keep their word and contribute to the community, no matter who their ancestors were.

The revival of Norse Paganism began in the 20th century and has grown steadily. In Scandinavia, organizations like the Íslenska Ásatrúarfélagið (Icelandic Ásatrú Association, founded 1972) and Forn Sed societies in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway have re-established the old religion in an official capacity. There are now Heathen communities and kindreds around the world, as well as many solitary practitioners. Modern Heathens often gather in groups to practice rituals under open sky, much as the Vikings did. At the same time, solitary practice at home is also common. Norse Paganism today is highly customizable: there is no single “one true way” to be a Heathen. Instead, there are core elements and beliefs shared by most practitioners, which we will outline next, along with the practices that bring those beliefs to life.

The Gods and Spirits of Norse Paganism

At the heart of Norse Pagan belief is a rich tapestry of deities and spirits. Practitioners are polytheists, meaning they honor multiple gods and goddesses, each with their own personality and domain of influence. The Norse pantheon has two tribes of deities, the Aesir and the Vanir, who live in the realms of Asgard and Vanaheim. In practice, Heathens don’t usually worry about tribal distinctions – Aesir and Vanir are all considered part of the divine family – but it can be useful to know some of the major figures:

- Odin – All-Father of the Aesir, god of wisdom, knowledge, poetry, and also war and death. He famously sacrificed himself on the World Tree Yggdrasil to discover the runes (symbols of wisdom and magic). Modern devotees look to Odin for guidance in wisdom, learning, and inner strength.

- Frigg – Odin’s wife, goddess of marriage, motherhood, and the home. A protector of families and a source of comfort and foresight.

- Thor – Son of Odin and god of thunder, protector of humanity. Thor is the archetype of strength, courage, and resilience. People invoke Thor for protection and to gain strength when facing challenges.

- Tyr – An ancient god of justice and heroic glory, known for his sacrifice of his hand to bind the chaos-wolf Fenrir. Tyr stands for honor, law, and bravery.

- Freyr (Frej) – A Vanir god of fertility, prosperity, sunshine, and fair weather. Freyr brings abundance and peace; farmers and those seeking prosperity often honor him.

- Freyja (Freyja) – Twin sister of Freyr, Vanir goddess of love, beauty, sexuality, seiðr magic (sorcery), and also a chooser of the slain in battle. Freyja is a complex goddess embodying passion and power; modern women and men alike revere her for empowerment, self-worth, and even help in finding love.

- Njord (Njörðr) – Father of Freyr and Freyja, Vanir god of the sea, winds, and coastal wealth. He is honored for safe travels, fishing, and prosperity from the sea.

- Heimdall, Bragi, Idun, Skadi, Balder, Eir, and many more – the Norse cosmos includes a wide array of deities. Each Heathen may feel drawn to different gods that resonate with their life. There is no requirement to honor all the gods equally; many people form special bonds with one or a few deities while respecting the rest.

Honoring the gods in Norse Paganism is less about worship in the distant, reverent sense and more about cultivating relationships. These gods are seen as powerful elder kin – wise and mighty beings who will work with you if you approach them with respect and reciprocity. Heathens often say they spend more time thanking the gods than asking them for favors. This reflects the Heathen ethic of reciprocity: you don’t just pray for help, you offer something of yourself (an offering, a promise, a toast) to build goodwill. Over time, through regular offerings and acknowledgment, you develop a personal rapport with the deities.

Modern devotional practice to the gods can be very simple and heartfelt. For instance, a beginner might pour out a small libation (liquid offering) to a deity and say a brief prayer of thanks. “Open a bottle of ale or cider (non-alcoholic is fine), go to a place in nature, take a few breaths, and say, ‘[Deity], I thank you for your many gifts,’ then pour out the liquid as an offering,” suggests one guide for new Heathens. Another common practice is to set aside a portion of your meal “for the gods” – put a small serving on a special plate and leave it outside overnight as an offering of gratitude. Lighting a candle and quietly meditating on a deity’s wisdom is also a powerful act of devotion. Through such practices, one thanks the gods for blessings like health, protection, or inspiration, and in return seeks their guidance or strength.

It is important to note that Norse Paganism is not about blind worship or fear of the gods. It’s a spiritual partnership. The lore often shows the gods as approachable and even fallible beings who appreciate honesty and courage from humans. For example, Thor is portrayed as a friend to mankind – a protector who enjoys a good drink and a hearty meal with his followers. Odin, while distant and enigmatic, values those who seek knowledge and better themselves. In modern practice, one might toast Thor in thanks when weathering a personal “storm” in life, or pray to Frigg for comfort and wisdom in caring for one’s family. These relationships with the divine can deeply enrich one’s life, providing a sense of companionship, meaning, and guidance. Many people find that talking to a deity in meditation or prayer can feel like talking to a wise mentor or beloved elder – it offers emotional support and insight. This can have direct mental health benefits: feeling heard and supported on a spiritual level can reduce loneliness and anxiety, and increase one’s confidence in handling difficulties.

Nature Spirits and Animism

Beyond the famous gods, Norse Paganism teaches that the world is alive with spirits of nature. Most Heathens are animists, believing that “everything has an inherent spirit”, from the Earth itself (the giantess Jord, mother of Thor) to the trees, rivers, rocks, and winds. In Norse folklore, these land spirits are sometimes called landvættir (land wights) or huldufólk (hidden folk/elves). They are subtle beings that inhabit natural features – perhaps a guardian of a particular forest, or a spirit of a mountain or lake. Even today in Iceland, belief in nature spirits runs so deep that road construction projects have been altered to avoid disturbing boulders said to be dwellings of elves, showing a cultural survival of respect for the land’s sentient presence.

For a modern Norse Pagan, connecting with nature spirits is a joyful and grounding practice. It starts with simply appreciating and respecting nature. Spend time outdoors, observe the changing seasons, and recognize that the earth is sacred. You can do small rituals to honor the local landvættir, such as leaving a biodegradable offering at the foot of a tree with a prayer of gratitude. This might be a bit of bread, a splash of milk or beer poured out, or flowers and herbs – given with a few words of thanks to the spirit of the place. Walking or standing barefoot on the earth, and mentally thanking the Earth (Jord) for her gifts, is another beautiful way to attune yourself to nature. When done regularly, these practices foster a deep sense of belonging in the natural world. Many people report that communing with nature in this way reduces their stress and improves their mood – modern science agrees that time in nature can soothe anxiety and uplift the mind. Norse Paganism encourages this by sacralizing nature: caring for the environment isn’t just a duty, it’s a form of reverence. It’s hard to litter or pollute when you believe the land itself has consciousness; indeed, “it is difficult to be disrespectful of nature when one is an animist”, as one practitioner put it. Thus, modern Heathens are often environmentally conscious, finding that caring for nature also feeds their own spirit.

Honoring the Ancestors

Another pillar of Norse spirituality is ancestor veneration. The ancient Norse held great respect for their forebears, believing that the dead could bless the living and that one’s family line was a source of strength. Today, most Heathens participate in some form of ancestor reverence, using the lives of their well-regarded ancestors as models and guides. This doesn’t require any specific heritage – everyone has ancestors, and Norse Paganism teaches that honoring your roots (wherever they lie) can be spiritually enriching. It’s about connection to your personal lineage and gratitude for those who came before, not about ethnic exclusivity. In practice, even an adoptee or someone disconnected from their family can engage in ancestor veneration by honoring symbolic or spiritual ancestors (for example, heroes or loved mentors who have passed on).

To venerate the ancestors, modern practitioners often create a simple shrine at home. This could be a shelf or tabletop with photos of your departed relatives, or heirlooms and mementos that remind you of them. You might light a candle there on birthdays or death anniversaries, or whenever you wish to feel their presence. Telling and remembering family stories is another way to keep your ancestors’ memory alive – in Heathen culture, immortality was achieved through being remembered in the sagas and songs. By sharing your grandmother’s favorite saying or your father’s life lesson with your children, you are continuing that tradition.

Heathens also sometimes include ancestors in their spiritual dialogue. For example, you might make a cup of tea and silently ask your ancestors’ advice on a problem. In a quiet meditation, imagine what wisdom a wise departed family member might offer – often, you will feel an answer arise in your heart. Some hold a periodic ritual known as Disablót (mentioned in lore as a sacrifice to the dísir, the female ancestral spirits) or simply toast their ancestors during a ceremony (like raising a glass “to the ancestors” in a rite). Such practices can provide a powerful sense of rootedness: you are not alone, but stand on the shoulders of generations. Especially in modern life, where many feel isolated or unmoored, developing an ancestral connection can strengthen your identity and resilience. Psychologically, it gives a comforting sense that your forebears are supporting you – a form of trans-generational social support. It can also inspire you; knowing what struggles your great-grandparents overcame can put your own challenges in perspective and motivate you to live up to their legacy.

In summary, Norse Pagan cosmology is populated by gods, nature spirits, and ancestors, all of whom can play a role in one’s spiritual life. A modern Heathen might pray to Thor for courage, leave offerings for the landvættir in a nearby wood, and light a candle for their grandmother’s spirit – all in the same week. This creates a rich spiritual ecosystem around the individual, providing multiple sources of guidance and comfort. Next, we will look at the practical rituals and activities by which Norse Pagans honor these beings and integrate this spirituality into daily life.

Norse Pagan Practices in the Modern World

One of the strengths of Norse Paganism is its practical, hands-on approach to spirituality. Rather than centering on belief alone, it emphasizes rituals, traditions, and lived experiences that bring the faith to life. Here are some core practices and how you can perform them in a modern context:

Modern Heathens often create simple outdoor altars for rituals. Here, a cloth on the ground and a driftwood figure of the sea-god Njord form a sacred space for a blót (offering ritual), connecting participants to the god and nature.

Blót: Offerings and Ritual Celebrations

Blót (pronounced “bloat”; Old Norse for “sacrifice” or “offering”) is one of the most important rituals in Norse Paganism. Historically, a blót involved a sacrificial offering to the gods or spirits – often an animal whose blood and meat were shared among the community and the deity. In Viking times, large blót feasts were held by chieftains to honor gods at key times like the start of winter or mid-summer, ensuring prosperity, victory, and good harvests. Animal sacrifice in ancient blóts was seen as a reciprocal gift to the gods (the people gave to the gods, and expected blessings in return) and a way to sanctify the communal feast.

Today, most Heathens do not perform animal sacrifices (except occasionally in groups of experienced practitioners, and if done, it is done humanely and the meat is eaten so nothing is wasted). Instead, modern blóts usually involve symbolic offerings of food, drink, or other gifts, followed by a shared meal. As one academic summary notes, “reconstructionist adherents of modern Germanic paganism have developed traditions of blót rituals… since the 1970s, [where] animal sacrifice is usually replaced with offerings of food or drink,” while still focusing on sharing food and strengthening relationships in the community. The social aspect – coming together in friendship, making toasts, and affirming community bonds – remains as essential as it was a thousand years ago.

A simple blót that anyone can do might go like this: Gather in a comfortable space (around an altar, or even a picnic table outside). Have some drink ready (mead, beer, juice, or water – whatever feels appropriate) and perhaps some bread or other food. Center yourself, and call upon the deity or spirit you wish to honor – for example, “We invite Thor to join our gathering and receive our thanks,” or “We honor the land spirits of this place.” You then make an offering: pour some of the drink into a bowl or onto the ground, or place the food on a plate or fire, as a gift to the unseen guests. As you do so, speak words of gratitude or praise (there’s no set liturgy – speak from the heart, or recite a relevant verse from the Eddas if you like). After the offering, it’s common to share the remaining food and drink among the participants, including a ceremonial toast where each person raises a horn or cup to the gods. This sharing affirms the idea that the gods and humans are feasting together, and it knits the participants into a tighter community.

One popular form of group ritual within many Heathen communities is the sumbel (or symbel), which is essentially a ritualized round of toasting. People sit in a circle, a horn of mead (or other drink) is passed, and each person in turn makes a toast or speech – often three rounds: one to the gods, one to the ancestors or heroes, and one personal toast (which could be an oath, a boast of something proud in one’s life, or an earnest toast for a wish/blessing). The sumbel is a powerful way of building camaraderie and speaking from the heart, and it can be emotionally supportive and empowering. For example, someone might toast Odin and say, “Hail Odin, may I have a small share of your wisdom as I start my new job!” – then on the ancestor round, they might raise the horn to a deceased mentor, “To my grandfather who taught me the value of hard work,” – and finally use the personal round to declare an intention, “I toast to my future success – I will finish my college degree this year. Hail!” The group honors each statement with a collective “Hail!” or some acknowledgment. This is both a spiritual and psychological exercise: by speaking your hopes and praises out loud in a respectful audience, you reinforce positive intentions and self-confidence, and gain support from your peers and the sacred forces.

Blóts can be tied to seasonal festivals as well. Most Norse Pagans celebrate a cycle of holidays that often align with the seasons and ancient Norse festival times:

- Yule (Jól) – The midwinter celebration around the winter solstice (late December). Yule is one of the biggest Heathen festivals, with feasting, lighting fires or Yule logs, and honoring the return of the sun’s light. Historically, Yule was a multi-day feast in midwinter; in the Viking calendar it might have been held in January, but today many celebrate from the solstice through New Year’s. Many Christmas traditions actually come from Yule (more on this later). Heathens hold blóts to Odin (who is closely associated with Yule as leader of the Wild Hunt) or to Frey/Freya for fertility and peace in the coming year. Sharing meals and even giving small gifts are common, since those customs were adopted into Christmas from pagan Yule.

- Þorrablót – In modern Icelandic tradition, a mid-winter feast (late January to February) honoring Thor and other gods, derived from medieval sources. Modern Heathens elsewhere sometimes hold a “Thor’s blot” in late winter to invite strength for the end of the harsh season.

- Ostara (Spring Equinox) – Many Heathens celebrate the spring equinox in late March, often honoring the Germanic spring goddess Ostara or simply marking the balance of day and night. Planting rituals or blóts for renewal are done.

- Walpurgis/May Day (April 30-May 1) – Known in some Germanic folklore as a night of magic (Walpurgisnacht). Heathens might honor the protective deities or land spirits as spring fully arrives.

- Midsummer (Summer Solstice) – The longest day (around June 21). This was indeed a significant time for the Norse: “Around 21 June, the Vikings held their midsummer sacrifice celebrations, on the year’s longest day we know as Midsummer’s Eve”, according to the Danish National Museum. Modern pagans celebrate the sun at its peak, often with bonfires, and might honor Sunna (the sun goddess) or Balder (a god associated with the summer sun and light). It’s a time of joy, gathering outdoors, and appreciating nature’s abundance.

- Freyr’s Blót / Loaf-Fest (early August) – Some hold a harvest-early festival, akin to Lammas, thanking Freyr and the earth for the first fruits of harvest.

- Autumn Equinox (Haustblót) – Around late September, giving thanks for the harvest and acknowledging the balance of light and dark as nights grow longer.

- Winternights (Vetrnætr) – In Old Norse tradition, the onset of winter (mid-late October) was marked by a festival often called Winter Nights or the Feast of the Einherjar. Modern Heathens may honor the ancestors and the valiant dead at this time, essentially a Norse Samhain, thanking ancestors as the veil thins.

- And then back to Yule.

Not every Heathen celebrates all these, and names for festivals can vary. But in general, keeping the seasonal holy days helps one connect with nature’s cycles, which can be very grounding. It creates a rhythm in life: you have something meaningful to look forward to every couple of months, where you gather with friends or perform a personal ritual to mark the turn of the wheel of the year. This in itself can improve well-being; it draws you out of mundane routine and gives moments of reflection, gratitude, and community.

Daily and Personal Practices

Aside from group rituals and big holidays, Norse Paganism offers many personal practices that individuals can integrate into daily life for spiritual growth and mental health. A few examples include:

- Morning or Evening Prayers/Meditations: You might start the day by greeting the sun (Sunna) with a quick prayer or end the day lighting a candle for the moon (Mani) or for your patron deity. Even saying “Hail Thor, protect me this day” as you put on a Thor’s hammer pendant can be a small ritual that imbues you with confidence and a feeling of protection.

- Home Altar: Maintaining a little altar or shrine in your home where you place symbols of the gods or nature (statues, stones, a bowl for offerings, etc.). You can stand before it to meditate, pray, or just collect yourself each day. This altar becomes a visual reminder of your values and sources of strength.

- Offerings and Thanks: As mentioned, pouring out a portion of your drink or setting aside a part of your meal occasionally as an offering is a nice habit. For instance, if you open a beer on a Friday night, you might pour a splash outside for Freyja (Friday is named after Frigg or Freyja) and say “Hail Freyja!” in thanks for the week’s blessings.

- Reading the Lore for Wisdom: Many find that reading a verse of the Hávamál (the “Words of the High One,” a poem of Odin’s wisdom) is a meditative practice. The Hávamál offers practical advice on how to live well and wisely. For example, it cautions against overindulgence and advocates hospitality, moderation, and courage. By studying such texts, one can glean ancient insights into handling modern problems. It’s like consulting a wise elder. Discussing a saga or myth with fellow pagans can also be enlightening and build community.

- Mindfulness in Chores: This might sound surprising, but even mundane tasks can become pagan practice. For instance, making bread can be an offering to the household gods or the goddess Frigg (who is associated with domestic arts). Tending a garden can be an act of honor to Earth and Freyr. Cleaning the house and then lighting incense or a candle to “reset” the space can be a little cleansing ritual. Approaching daily life in this mindful, reverent way can transform stress into something meaningful – chores become rituals that symbolically clean and order your inner world too.

Meditation, Trance, and Magic

Norse Paganism has a magical and mystical side as well. In the myths, there are shamans and seeresses (like the famous völva in saga accounts) who could enter trances, see the future, or work magic (called seiðr and galdr in Old Norse). Modern practitioners sometimes explore these aspects through meditation, visualization, chanting, and journeying techniques.

Meditation in a Heathen context might involve visualizing one of the Nine Worlds or the World Tree, or simply quieting the mind to be open to the gods’ messages. A simple meditation is to sit quietly, breathe deeply, and “ask the gods to share their wisdom with you,” then spend time listening in silence. Often, as the spirituality guide notes, you will “hear” wisdom come from the still center of your heart – essentially your subconscious or intuition presenting insight, which you attribute to divine guidance. This is a calming practice that builds inner listening and can reduce anxiety.

Some Norse Pagans practice guided visualizations or trance-journeys where they imagine traveling in the realm of spirit – for example, journeying to meet an ancestor or an animal spirit, or to ask Odin a question in a visualized Asgard. These practices, similar to shamanic journeying, can be profound but typically require training or guidance to do safely. Even breathwork and rhythmic chanting can induce a light trance state that is very soothing. In fact, research on trauma healing has found that focused breathing and trance-like states can help integrate mind and body and promote well-being. It’s fascinating that many pagan ritual techniques (deep breathing, drumming, chanting, dancing) naturally produce therapeutic effects: they increase heart-rate variability, lower stress, and foster feelings of calmness and inner strength. So when a Heathen drums and chants a rune name for 10 minutes, they might not only feel closer to the divine, but also physiologically reduce anxiety and improve mood.

One accessible magical practice is galdr, the chanting of rune sounds or songs. For example, intoning the name of the rune “Algiz” repeatedly in a low voice while visualizing a protective elk spirit can create a feeling of safety and an almost meditative focus. Some also compose or use simple chants to the gods. For instance, chanting “Earth below, sky above, runic power, fill with love” while meditating on the interconnectedness of all things. Such creative, intuitive spiritual exercises are encouraged – there is no strict dogma, so you are free to experiment with what rituals or chants help you feel spiritually connected and psychologically centered.

Runic Work for Insight and Healing

No discussion of Norse Pagan practice is complete without mentioning the runes. The runes are the ancient alphabets (such as the Elder Futhark) used by Germanic peoples. Beyond writing, runes were historically used for magical purposes, divination, and symbolism. In modern Norse spirituality, working with runes is a popular way to gain insight, meditate, and even do a bit of magic for personal growth.

Each rune is more than a letter – it’s a symbol with a name and meaning (for example, Fehu means cattle/wealth, Algiz means elk/protection, Sowilo means sun/victory, etc.). According to myth, Odin’s sacrifice of hanging on the World Tree for nine nights granted him a vision of the runes and their powers, which underscores their divine significance. Today, many Heathens use runes as a divination tool similar to tarot. One might “cast the runes” by drawing a few from a pouch at random and interpreting how their meanings apply to a question or situation. This practice can be “a bridge to the past and a path to inner wisdom,” helping to tap into your subconscious and reveal insights. Because each rune triggers certain associations (e.g. Uruz might evoke strength, health, raw power), contemplating runes can guide you to think about aspects of your life you might otherwise ignore. In this way, rune reading becomes a powerful tool for introspection and decision-making in daily life. For example, if you draw the rune Raidho (which signifies a journey or change), you might reflect on how to navigate an upcoming life transition in an orderly, honorable way – the rune acts as a prompt for constructive thought.

A set of painted Elder Futhark runes on stones. In Norse Pagan practice, runes are not only an ancient alphabet but also symbols of mystic power and meaning. Working with runes through casting or meditation offers a “bridge to the past” and a path to inner wisdom, helping practitioners gain insight and guidance in their life’s journey.

There are many ways to work with runes beyond casting lots for divination. Some people do rune meditations – focusing on one rune’s shape and sound, and seeing what thoughts or imagery arise. This can be illuminating; for instance, meditating on Laguz (water, flow) might help you realize you need to go with the flow in a certain situation instead of fighting it. Others create bind-runes (combining two or more runes into a single symbol) to serve as talismans or sigils for a desired outcome. For example, combining Algiz (protection) and Tiwaz (the Tyr rune for justice) and carrying it as an amulet in court for a fair legal outcome. The act of creating a bind-rune with a clear intention can be psychologically empowering – it’s a tangible focus for your will and hope.

Some also use runes in holistic healing or self-care contexts. Writing a rune on a bandage or casting runes to ask “What do I need to heal?” can engage your mind in the healing process. One of the Norse gods, Eir, is a goddess of healing, and a modern practitioner might invoke Eir and draw the Uruz rune (vitality) over themselves when feeling ill, as a form of positive visualization and comfort.

Working with runes thus serves both a spiritual purpose (connecting with the wisdom of Odin and the Norns, perhaps) and a psychological one (freeing your intuition and highlighting factors you should consider in a decision). Many find that even if one is skeptical of “fortune-telling,” rune work is valuable as a mirror for the mind – the symbols you pull often make you think in new ways. For example, pulling Isa (ice, standstill) when frustrated about a lack of progress could make you realize this is a natural pause and that patience is needed; pulling Kenaz (fire, creativity) could spur you to try a creative solution you hadn’t considered. In this way, the runes act as counselors.

Embracing Community and Creativity

Modern Norse Paganism isn’t just rituals and introspection – it’s also about community and culture. Many Heathens find meaning and mental health benefits in the fellowship and activities that surround the faith. Groups called kindreds or sibs often form, which are like extended spiritual families. These groups might meet for blóts and sumbels, but also for casual get-togethers, crafting, hiking, or projects. The sense of belonging to a community that shares your values can be deeply rewarding, especially in a world where one might feel isolated. In Heathen communities, there is an emphasis on hospitality and taking care of each other, echoing the Viking-age practices. Good Heathens strive to be the kind of friend who will offer you a meal, a towel if you stay over, and a listening ear when you’re troubled. Knowing you have that kind of community support is hugely beneficial for mental wellness. It builds trust and a safety net of people you can rely on, which bolsters resilience against life’s stressors.

Norse Pagan culture today also encourages creative pursuits that connect to the old ways. This in itself can be therapeutic. Some Heathens are inspired to brew their own mead (harkening to the “mead of poetry” in Odin’s myth, and enjoying a creative hobby). Others take up crafting, woodcarving, forging, or sewing to recreate historical items or simply to bring the runes and symbols into tangible form. There’s a resurgence of interest in fiber arts (spinning, weaving) as a nod to the Norns or Frigg (who spins destiny). Storytelling and poetry are also big – some write new sagas or poems about the gods. Engaging in these creative arts can bring joy and a sense of accomplishment, as well as connect you to ancestors who did these things. It’s well known that creative expression and hobbies are good for mental health, reducing anxiety and improving mood. In a Heathen context, your art or craft also becomes imbued with spiritual meaning, which adds a fulfilling dimension.

Finally, there is joy and empowerment to be found in living according to Norse Pagan ideals. For instance, by striving to embody virtues like courage, truth, and perseverance, you may find yourself overcoming personal hurdles that once daunted you. The myths provide inspiring role models: Odin’s ceaseless quest for wisdom despite sacrifice, Thor’s determination to protect the innocent, Freyja’s unabashed ownership of her power and sexuality, Tyr’s bravery to do what is right even at great personal cost, and so on. These stories can be a reservoir of strength. When facing difficulties, a Heathen might recall the trials of their gods and heroes – if Ragnarök (the final battle) can be faced with valor, surely I can face my smaller challenges with courage and a smile. This perspective can foster a kind of stoic resilience and acceptance of hardship, combined with proactive effort to meet one’s fate honorably. In psychological terms, that’s a very adaptive mindset: it reduces the fear of failure (since even the gods meet their fates) and encourages one to focus on how you live and fight, rather than worrying about what you cannot control.

Spiritual and Mental Health Benefits of Norse Pagan Practice

Norse Paganism, like many spiritual paths, offers not only metaphysical beliefs but also concrete benefits for one’s mental and emotional well-being. In fact, many who turn to this path find that it helps them become happier, more grounded, and more resilient individuals. Here are several ways in which practicing Norse Paganism can enhance holistic well-being:

- Connection and Belonging: By worshipping the Norse gods, honoring ancestors, and communing with nature, practitioners often feel deeply connected – to their past, to the Earth, and to a wider spiritual family. This sense of belonging can counteract the loneliness and alienation that are so common in modern society. Participating in group rituals bolsters “feelings of trust, belonging, and support from others”, which is a known protective factor for mental health. Simply put, you feel like part of a tribe – whether it’s an actual local group or just an online community of fellow pagans – and that social support improves life satisfaction and reduces stress.

- Meaning and Purpose: Having a spiritual framework provides meaning in life. Norse Paganism gives you a heroic narrative to partake in – life is seen as a saga where your deeds matter (your honor and reputation “never die” as Odin says in the Hávamál). Striving to better yourself and to help your community, as Heathen ethics encourage, can imbue your day-to-day activities with purpose. Even small acts, like making an offering or keeping an oath, become meaningful. Psychologically, this combats feelings of nihilism or aimlessness. Purpose is strongly tied to mental health; it keeps one motivated and positive even in hard times.

- Inner Strength and Resilience: Norse Pagan practices train inner qualities that build mental resilience. Meditation and ritual teach focus and calm. Making oaths and living by virtues develops self-discipline and integrity. Encountering the myths – where even gods must face destiny with courage – can shift one’s perspective on personal struggles, fostering a more resilient outlook. Participating in ritual can also be cathartic: through symbolic actions, you process emotions (for example, burning an effigy of what you want to let go of in a fire at Yule, representing the return of light). Many pagans report that rituals help them process grief, mark life transitions (like weddings, funerals, coming-of-age) in a healthy way, and release emotional burdens. This is akin to a form of group therapy in some cases, but sanctified.