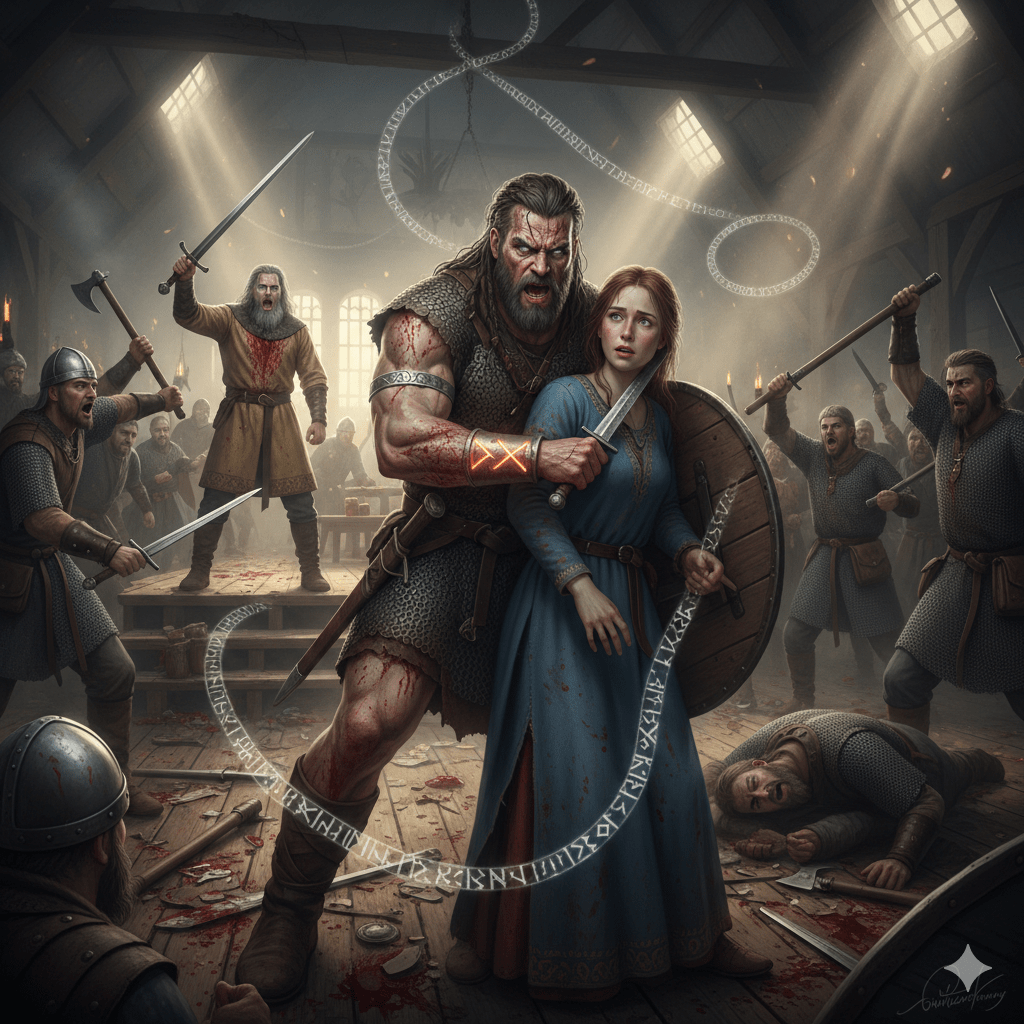

Sample of AI GMed Norse Saga Engine Combat 2

Your berserkergang ignites like Fenrir unchained, Volmarr Ragnarsson-eyes wild with eight winters’ frozen rage, gray-blue fire amid blood-matted braids, father’s silver arm-ring flashing as Raidho’s rune pulses hot on your skin. Seax gripped iron-tight (your “sword” in frenzy’s blur), you *charge* through the huskarl snarl, shield bashing a path toward Inga’s fleeing shadow, low HP fueling mad drengskapr (reckless Dash crashes the melee; opportunity axes rake your flanks-12 slashing wounds tear chain-shirt and flesh, vigor shattering to 0/28). Pain blacks the edges, yet wyrd hurls you onward, Second Wind surging reflexive (1d10+3=9 HP regained; ragged breath claws you to 9/28, blood bubbling from thigh-gash and rib-rents).

Huskarls howl outrage-*\”Ulfhedinn! Wife-slayer-níd upon the dog!\”*-their ring-mail wolves parting blood-slick just enough as your frenzy bowls two aside (one crumples greataxe-down, 10 wounds; pack reforms iron-thick). Dawn shafts pierce smoke-holes, gilding the trampled rushes slick with gore, iron-tang choking the wool-reek as overturned benches splinter under boot-thud. You crash into the side-chamber threshold, gauntleted hand snaring Inga’s embroidered kirtle mid-flight-her amber brooch snaps free, clattering like shattered oath-yanking her frail form back against your bloodied chest. Seax kisses her pale throat, edge nicking pearl-skin (grapple holds; she freezes, AC 10 no match for berserk grip), her shriek dying to whimper: *\”Mercy, wanderer-Frigg shield me! No hall-blood on kin… please, gods…\”* Wide hazel eyes plead terror, frail hands clawing air, no shieldmaiden’s steel but a noble’s fragility, her breath hitching with secrets unspoken.

The hall freezes mid-chaos, embers hissing judgment. Eirik Jarl erupts from dais-edge, neck-gash crusted crimson down gold-broidered tunic, cold blue eyes arctic murder beneath gray-streaks. His masterwork longsword rises, Battle Master poise venomous, voice thundering lordly doom laced in tyrant’s glee: *\”Ulfhedinn filth! Nídingr deepest-jarl’s wife under blade? Guest-right dust, your \u00e6ttar s\u00f3mi shamed eternal! Wolves-*take* the chaff alive for Thing’s slow gibbet, let freemen see Ragnar’s whelp twist!\”* Twenty-odd huskarls surge convergent, axes hammering your shield to ruin (disadvantage bites reckless rage), swords thirsting for hamstring and yield. One clips your sword-arm (4 slashing; down to 5/28), another pommels your skull (stun reels you), the pack’s ordstírr a noose tightening.

Inga trembles blade-kissed, tears carving tracks: *\”Eirik-truth for my breath? Byzantine shades… Ragnar knew… mercy!\”*-whisper half-heard ere steel rains. Wyrd coils lethal: níd brands you wolfskin outlaw, blood-feud with Eirik’s kin awakened, Freyja’s curse on wife-assailant, hall-sanctity shattered beyond mend. Reinforcements boot-thud from yards, your handaxe sheathed desperate throw, frenzy ebbing to exhaustion’s bite. Seax quivers at her neck-demand Eirik’s confession now? Release and hurl truths to sway any wavering? Fight the swarm till bones break? Yield and spit proofs for Thing’s mercy? Or bolt with hostage through side-dark? The Norns knot tight, Volmarr-thread your defiance ere wolves devour.

Sample of AI GMed Norse Saga Engine Combat

Your seax-father Ragnar’s sharp legacy, still slick with the jarl’s blood-whirls in your grip like Raidho’s furious path, Volmarr Ragnarsson, as you wrench your round shield high and unleash wide, sweeping arcs through the snarling huskarl pack. Dawn’s pale shafts lance the smoke-hazed hall, gilding sweat-slick faces and bared iron, the air a choking reek of blood-iron, trampled rushes, and the sour bite of fear. Eight winters’ wyrd erupts in your veins, drengskapr turned berserk frenzy; your gray-blue gaze burns past the ring-mailed wolves, fixing on Eirik as you hurl your spear like Odin’s own javelin, shaft whistling for his crowned skull.

The first sweep bites deep-a burly axe-man’s throat opens in a crimson fan (critical stroke on the wind’s edge; huskarl crumples lifeless, 12 wounds claimed), his ring-mail parting like wet wool. Your Action Surge surges hot, a second arc cleaving another’s sword-arm at the shoulder (8 slashing; he howls, staggering back blood-drenched but standing, axe clattering). The spear flies true in intent but glances wild off Eirik’s upflung pauldron (ranged strike foiled by chaos’ sway; 14 misses AC 18), embedding quivering in the high-seat’s carved flank amid splintered oak. Two foes felled or broken amid two dozen-yet the pack closes relentless, their ordstírri-bound fury a tide no lone wanderer stems.

Eirik Jarl snarls from the dais’ edge, neck-gash weeping scarlet down his gold-broidered tunic, cold blue eyes blazing with tyrant’s wrath beneath gray-streaked hair. *”Nídlingr! Hall-slayer-your father’s ghost weeps at such chaff!”* His masterwork longsword leaps free, Battle Master precision uncoiling: a riposte feints low then surges (15 misses your shield’s desperate brace), but his command lashes louder: *”Wolves, crush the oathbreaker-alive for the Thing’s gibbet!”*

The huskarls swarm like Jörmungandr’s thrash-six blades converge in the tight melee, axes and swords hacking through dawn’s gloom. A greataxe bites your thigh past shield-rim (7 slashing), another sword gashes your ribs (6 piercing through chain-shirt gaps), a third clips your helm-scalp (4 slashing). Pain blooms fire-hot (17 total wounds; your vigor bleeds to 6/28, blood sheeting your braided locks and silver arm-ring, vision blurring red). Inga shrieks from the shadows, her kirtle aflutter as she bolts for the side-chambers: *”Thor curse this hall-blood-mercy, gods!”*-her flight a pale blur amid overturned benches and scattered mead-horns.

Embers hiss under boot-stomp, steel-song drowns all roars, the great hall a churning pit of wyrd’s spite. Twenty-two huskarls circle iron-tight, Eirik poised for the kill-stroke (54/60 vigor unbowed), reinforcements’ boots thundering from outer yards. Your seax drips victory’s scant toll, Second Wind a ragged breath away, handaxe yet sheathed for desperate throw-yet níd’s brand sears your name eternal: outlaw chaff, kin-shame without witness or oath. Bolt for the doors through the press? Rally with final surge? Surrender truths amid the steel rain? The Norns’ thread frays thin, Volmarr-what defiance do you weave?

The Loom is Spinning: Enter the Norse Saga Engine

The sagas of old were carved in bone and stained in red—now, they are forged in code.

The Norse Saga Engine is a groundbreaking RPG experience that uses real-time AI to weave a living, breathing Viking world around your every choice. This isn’t a sanitized fantasy; it is a hyper-realistic dive into the grit of the Viking Age, where history, folklore, and the whispered secrets of the runes collide.

What Awaits You:

- True Authenticity: Built on a foundation of genuine Norse lore, religious practices, and the complex social structures of the era.

- Visceral Interaction: Advanced, adult-oriented AI characters that respond with human-like nuance, memory, and depth.

- The Power of Seiðr: A low-fantasy world where magickal practices and Norse spirituality aren’t just mechanics—they are the atmosphere.

- Novel-Quality Narrative: Every session generates an interactive historical fiction masterpiece, tailored to your path.

The Norns are weaving a new thread, and the architecture of the soul is being mapped. This project is developing rapidly—prepare to claim your place in the saga.

Stay tuned. The high tide is coming.

DIY Small Simple Viking Longhall on Budget

⚒️ Overview of the project

A simple longhall inspired by Viking design:

- Size: modest — e.g. ~16 feet x 10 feet (5m x 3m), enough for gatherings, feasts, or rituals.

- Structure: timber frame with post & beam (no complex joinery needed), using logs or squared timbers.

- Walls: vertical plank, wattle & daub, or log walls.

- Roof: simple gable with locally sourced poles + thatch, turf, or wooden shingles.

🌲 Preparing your wood

Since you’re sourcing from your own land:

- Use straight young trees for posts & beams (oak, ash, hickory, pine).

- Select green wood, easier to shape. Avoid rotted or insect-damaged logs.

- Debark them to avoid insects & help drying.

Basic shapes:

- Posts: ~6-8″ diameter (15-20 cm), stripped logs

- Beams & rafters: ~4-6″ (10-15 cm)

- Planks or split boards: for walls or roof

🪓 Tools you’ll need

- Axe (for felling & rough shaping)

- Drawknife or spoke shave (for debarking & smoothing)

- Saw (chainsaw or handsaw)

- Auger or drill

- Hammer & nails (or wood pegs if you want to go traditional)

- Optional: adze or hatchet for shaping flat surfaces

🏗️ How to build it

1. Lay out your ground plan

- Stake out a rectangle, e.g. 16’ x 10’.

- Set corner stakes, use cord to make sure it’s square.

2. Dig post holes

- About 3 feet deep for corner posts + center posts if needed (depending on snow load & soil).

- Place vertical posts, backfill with stones & soil, tamp down firmly.

3. Add horizontal beams (wall plates)

- Lay beams across tops of posts, secure with lap joints or simply with heavy screws / wooden pegs.

- Lash with strong cord or use steel brackets if traditional pegs are too tricky.

4. Roof framing

- Run a ridge pole along the center line on top of posts.

- Set rafters leaning from wall beams up to ridge pole.

- Lash or nail rafters.

5. Roof covering

Options:

- Thatch: bundle reeds, straw, or grasses and tie them to horizontal battens.

- Wood shingles: split from logs with a froe & mallet, nail on overlapping.

- Turf: layer birch bark over boards, then cut sod on top.

6. Wall infill

Three simple Viking-appropriate methods:

- Plank walls: nail vertical planks to horizontal sills & beams.

- Wattle & daub: weave small branches between stakes, smear clay+straw mix.

- Log walls: stack small logs with notches or simply spike them together.

7. Floor

- Leave dirt floor, or tamp gravel.

- Could add simple wood planks if desired.

8. Finishing touches

- Carve or burn runes on lintels.

- Hang shields, weapons, or ritual objects.

- Build a central fire pit (with vent hole in roof or smoke hole).

💡 Tips for keeping costs minimal

✅ Harvest all wood yourself.

✅ Use clay or cob from your own land for daub.

✅ Use stone from your property for post packing or hearth.

✅ Scavenge old nails / metal from barns or pallets.

✅ Learn simple lashings with natural rope (hemp or jute).

🐺 Viking soul — modern tools

- Even though Vikings used axes & adzes, you can use a chainsaw for quicker cuts.

- Use battery drills to drive big screws or lag bolts instead of traditional wooden pegs if that’s more practical.

🌿 In short

- Simple post-in-ground structure.

- Natural wood + basic joinery or lashings.

- Walls of planks or wattle & daub.

- Roof of local thatch, turf, or split shingles.

This creates a humble yet powerful Viking longhall, alive with the spirit of your own land. 🌙

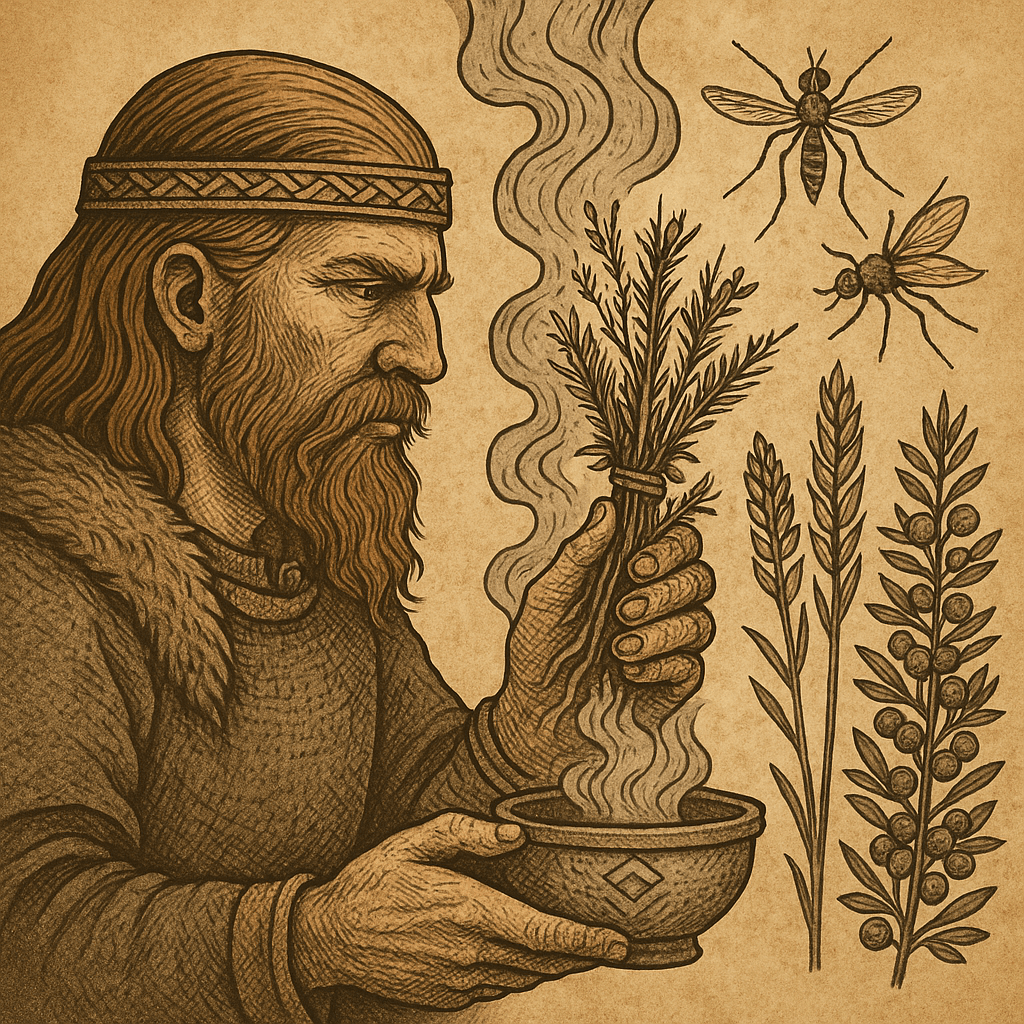

Did the Vikings Use Incense As Bug Repellent?

🌿 Evidence from ancient cultures generally

Many ancient societies across Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas used smoke from burning herbs, woods, and resins to drive away insects. This served multiple functions: ritual purification, offerings to gods or spirits, pleasant scenting of spaces, and practical repelling of biting insects.

Examples include:

- Ancient Egyptians burned frankincense and myrrh, which also helped keep away flies and mosquitoes.

- In India, burning neem leaves or other pungent herbs was traditional to repel insects.

- Indigenous groups across Africa and the Americas burned local plants specifically because the smoke drove off mosquitoes and flies.

🪵 Viking & broader Norse practices

For the Vikings and their ancestors in the Germanic world, direct references to using incense specifically as bug repellent are scarce in written sources, largely because most of their literature (like sagas or Eddic poetry) wasn’t interested in such domestic details.

However, archaeological and ethnobotanical studies, plus later Scandinavian folk practices (often thought to preserve older traditions), suggest:

- Juniper (Juniperus communis) was frequently burned. It was used ritually for purification, but the smoke also naturally drives away insects and was used to fumigate dwellings and barns.

- Mugwort, yarrow, and angelica were sometimes burned or hung in homes and on doorways. These herbs have insect-repelling properties.

- In the Viking Age, longhouses had central hearths burning constantly. This smoke would naturally deter mosquitoes and other insects.

Even if they did not burn herbs solely for insect control, the practice of fumigating spaces with aromatic herbs for blessing or cleansing often had the secondary effect of driving out pests.

🔥 Broader idea of “incense”

For the Vikings, “incense” as understood in the Roman or later Christian sense (fine imported resins burned in censers) wasn’t typical. However, they did burn local herbs, wood chips, and even resins from conifers (like pine and spruce) on hearths and fires, both inside and in ritual contexts outside. This fits the broader concept of incense: aromatic smoke for spiritual and sometimes practical purposes.

✅ Conclusion

So while we don’t have a saga quote like:

“And so did Bjorn burn mugwort in the longhouse to chase away the biting flies…”

—we do have:

- Archaeological evidence of burned herbs and resinous woods.

- Ethnobotanical records showing continuity into later Scandinavian traditions of burning juniper and herbs to cleanse and drive off pests.

- A general human pattern across ancient cultures of burning plants that happen to repel insects.

Thus, it’s highly likely the Vikings and other ancient Northern Europeans benefited from the insect-repelling side effects of burning aromatic plants—whether or not that was always their main intent.

🌿 Herbs, woods, and plants used in Viking Age or broader Norse / Germanic lands

🔥 Juniper (Juniperus communis)

- 🔸 How used: Bundles or branches thrown into hearth fires, or smoldered in braziers.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Flies, mosquitoes, fleas, lice.

- 🔸 Notes: Still burned in Scandinavian farmhouses to “smoke out” pests & purify air.

🔥 Mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris)

- 🔸 How used: Burned as smudge sticks or strewn on coals.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Moths, fleas, mosquitoes.

- 🔸 Notes: Also used magically to protect against evil spirits.

🔥 Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

- 🔸 How used: Smoldered on coals or hung in bunches by doors & beds.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: General flying insects.

- 🔸 Notes: Valued for both wound-healing and as a pest deterrent.

🔥 Angelica (Angelica archangelica)

- 🔸 How used: Leaves or seeds burned on hearths.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Flies, gnats.

- 🔸 Notes: Sacred plant in Norse tradition, linked to protection.

🔥 Birch (Betula spp.)

- 🔸 How used: Birch wood was common fuel. The aromatic smoke helped keep insects away.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Flies, mosquitoes.

- 🔸 Notes: Birch tar itself is insecticidal and antiseptic.

🔥 Pine & Spruce resins

- 🔸 How used: Resin (pitch) tossed onto fires to produce fragrant smoke.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Mosquitoes, midges.

- 🔸 Notes: Also used to waterproof ships, showing the resin was widely collected.

🔥 Bog myrtle / Sweet gale (Myrica gale)

- 🔸 How used: Sometimes burned, also stuffed into bedding.

- 🔸 Insects repelled: Fleas, lice.

- 🔸 Notes: Used in brewing as well — an herb for ale before hops.

🪶 Types of insects typically targeted

- 🦟 Mosquitoes & midges: Common in Scandinavian summers near fjords & wetlands.

- 🪰 Flies: A major nuisance in longhouses where livestock shared living spaces.

- 🪳 Fleas & lice: Burning fumigants helped cleanse bedding and clothing.

- 🐛 Moths: Protected stored woolens & furs.

🌬️ Practical & mystical crossover

In Norse culture there was often no hard line between “practical fumigation” and ritual. Burning juniper or mugwort could be a spiritual cleansing that also chased away fleas — a perfectly pragmatic kind of magic.

📝 Little pro tip if you want a modern Viking-style bug repellent

Try bundling dried juniper, mugwort, and a little pine resin, tie it with natural twine, and burn it in a safe outdoor fire pit. The smell is ancient and haunting — and it still works remarkably well on flies and mosquitoes.

Did the Vikings Use Wooden shingles?

✅ Yes, Vikings did use wooden shingles, especially in areas rich in timber like Norway and Sweden.

They were not the only roofing method (thatch was more common for ordinary farms), but shingles were indeed used for more durable or prestigious buildings.

How did the Vikings make and use shingles?

➤ Materials

- They used pine or spruce, common in Scandinavia, which splits well along the grain.

- The wood was usually air dried, sometimes lightly seasoned by storage.

➤ Shaping

- Vikings split shingles (rived them) using axes or froes, rather than sawing.

- Splitting follows the wood’s natural grain, making shingles stronger and less prone to warping.

- Shingles were typically thin, tapered, and around 30-60 cm (1-2 feet) long, depending on the building.

➤ Installation

- They were laid in overlapping rows, each course covering the top of the one below it to shed rain and snow.

- Vikings would fix them with wooden pegs or iron nails.

- Roofs were built steep to help snow slide off, which worked well with shingle construction.

Where do we see evidence of this?

- Archaeology: Traces of wooden shingle roofs have been found at Norse sites in Norway and Sweden. Some post-Viking stave churches (12th century onward) still use nearly identical techniques that evolved directly from Viking-age practices.

- Saga & law texts: While most Viking-era writings don’t give explicit blueprints, later medieval Scandinavian laws do mention shingle roofs, implying a long tradition.

- Living tradition: In parts of Norway, wooden shingle craftsmanship is still practiced in much the same way, with strong links back to Viking wood-working culture.

Summary

So yes: the Vikings used wooden shingles.

They made them by splitting timber along the grain, shaping them into thin tapered tiles, and laying them in overlapping rows on steep roofs, secured with wooden pegs or nails. While thatch was more common for everyday farmsteads, wooden shingles were a respected choice for halls, wealthier homesteads, and later for churches — a direct continuation of Viking building traditions.

Why Strict Reconstructionist Norse Paganism Is Roleplay—Not a Living Spiritual Practice for Most

In the world of Norse Paganism, there’s a growing tension between two very different approaches: strict reconstructionism and modern spiritual adoption. At first glance, both claim to honor the gods and revive ancient ways—but scratch the surface, and their core intentions begin to sharply diverge.

Strict reconstructionists attempt to practice Norse Paganism as close as possible to how it was performed over a thousand years ago. Their goals are often academic and historical in nature—following archaeological records, scholarly interpretations, and surviving lore as strictly as possible. From the type of mead poured in ritual to the precise reconstruction of Iron Age clothing or burial rites, the focus is often on reenacting history with accuracy. In truth, this approach has more in common with living history roleplay than with a living, breathing, evolving spiritual path.

And that’s not inherently a bad thing. Some people do connect deeply with the spiritual dimension through historical reenactment. For them, reconstructing ancient rituals and customs may feel reverent and grounding. But it’s important to acknowledge that this is not the only, nor the most accessible, way to walk a spiritual path rooted in the Norse tradition.

Reconstructionism as Spiritual Roleplay

Let’s be clear—roleplay is not an insult. It is a legitimate form of expression. Historical reenactors often feel transformed when donning the clothes and manners of a bygone time. But that transformation is often theatrical and symbolic, not existential. The strictest forms of Norse Pagan reconstructionism fall into this category. They aren’t really meant to function as a religious practice that addresses modern human needs—emotional healing, personal growth, mystical connection, or guidance through trauma, anxiety, or love. They’re meant to recreate the past as closely as possible. In this, they function more like immersive theater or participatory anthropology.

To the average person seeking spiritual depth, comfort, insight, or healing, this “museum exhibit” approach offers little. It risks becoming a cage of historical fetishism, where one’s personal gnosis is dismissed because it didn’t come from a 13th-century Icelandic manuscript. This strict gatekeeping often stifles the organic, transformative nature of religion, which has always adapted to new cultural contexts throughout history.

The Need for a Living Spiritual Practice

Living spirituality is not frozen in time. It grows with the people who walk it. Modern Norse Paganism must be allowed to breathe—to evolve in the hearts of those who embrace it, integrating the ancient with the modern, the mythic with the mystical, and the historic with the intuitive. After all, the gods themselves are not dead cultural relics. They are living autonomous spiritual beings, beings of great power, meaning, and presence that people can still feel, dream of, and be transformed by today.

The modern world brings different needs than the Viking Age. We wrestle with urban alienation, ecological collapse, neurodivergence, spiritual longing in an age of disconnection, and a search for meaning beyond corporate modernity. We don’t need a historically perfect blot in a longhouse to find sacredness—we need connection, authenticity, and soul-level truth.

A living Norse Pagan practice honors the spirit of the old ways without being enslaved to their letter. It welcomes offerings from today’s world: meditation, trancework, modern rituals, cross-cultural influences, even VR temple spaces or AI rune readings—if they bring the seeker closer to the divine. It dares to believe that Odin, Freyja, and the spirits of the land are not frozen in the Viking Age, but walk beside us now, adapting with us.

There’s Room for Both—But Let’s Be Honest About What They Are

There is nothing wrong with practicing Norse Paganism as living-history roleplay. It can be fun, educational, and even meaningful. But it should not be confused with a universal path to spiritual transformation. Most people today are not looking for perfect historical reenactment—they are looking for purpose, power, belonging, and divine connection. That calls for something alive, not just accurate.

In the end, both paths—strict reconstruction and adaptive spirituality—have their place. But for the majority of spiritual seekers, the gods do not demand authenticity to the 10th century. They ask for sincerity of the heart, integrity of intent, and the courage to meet them here and now, in the sacred space of this age.